|

||||||||||||||||||||||

![Home - Air Power Australia Website [Click for more ...]](APA/APA-Title-Main.png) |

||||||||||||||||||||||

![Sukhoi PAK-FA and Flanker Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/flanker.png) |

![F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/jsf.png) |

![Weapons Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/weps.png) |

![News and Media Related Material Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/media.png) |

|||||||||||||||||||

![Surface to Air Missile Systems / Integrated Air Defence Systems Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/sams-iads.png) |

![Ballistic Missiles and Missile Defence Page [Click for more ...]](APA/msls-bmd.png) |

![Air Power and National Military Strategy Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/strategy.png) |

![Military Aviation Historical Topics Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/history.png)

|

![Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance and Network Centric Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/isr-ncw.png) |

![Information Warfare / Operations and Electronic Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/iw.png) |

![Systems and Basic Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/technology.png) |

![Related Links Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/links.png) |

|||||||||||||||

![Homepage of Australia's First Online Journal Covering Air Power Issues (ISSN 1832-2433) [Click for more ...]](APA/apa-analyses.png) |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Last Updated: Mon Jan 27 11:18:09 UTC 2014 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Strategic SAM Deployment in

Iran

|

| Technical Report APA-TR-2010-0102 Sean O'Connor, BA, MS (AMU) January 2010 Updated April, 2012 Text © 2009 Sean O'Connor Line Artwork, Layout © 2009 - 2012 Carlo Kopp  |

|

|

Introduction/BackgroundWith the current attention being given to potential Iranian

nuclear weapons development, it is prudent to examine the defensive

posture of the Persian state in light of potential military action.

This article will focus on Iran's strategic SAM deployment. Three

different strategic SAM types, along with two tactical SAM types,

provide sporadic, yet still potentially effective, SAM coverage

throughout the nation. Unusual deployment strategies hint at what may

be part of a serious deception campaign, possibly providing insight

into the apparent lack of serious, integrated ground-based air defense

coverage throughout most of the nation. |

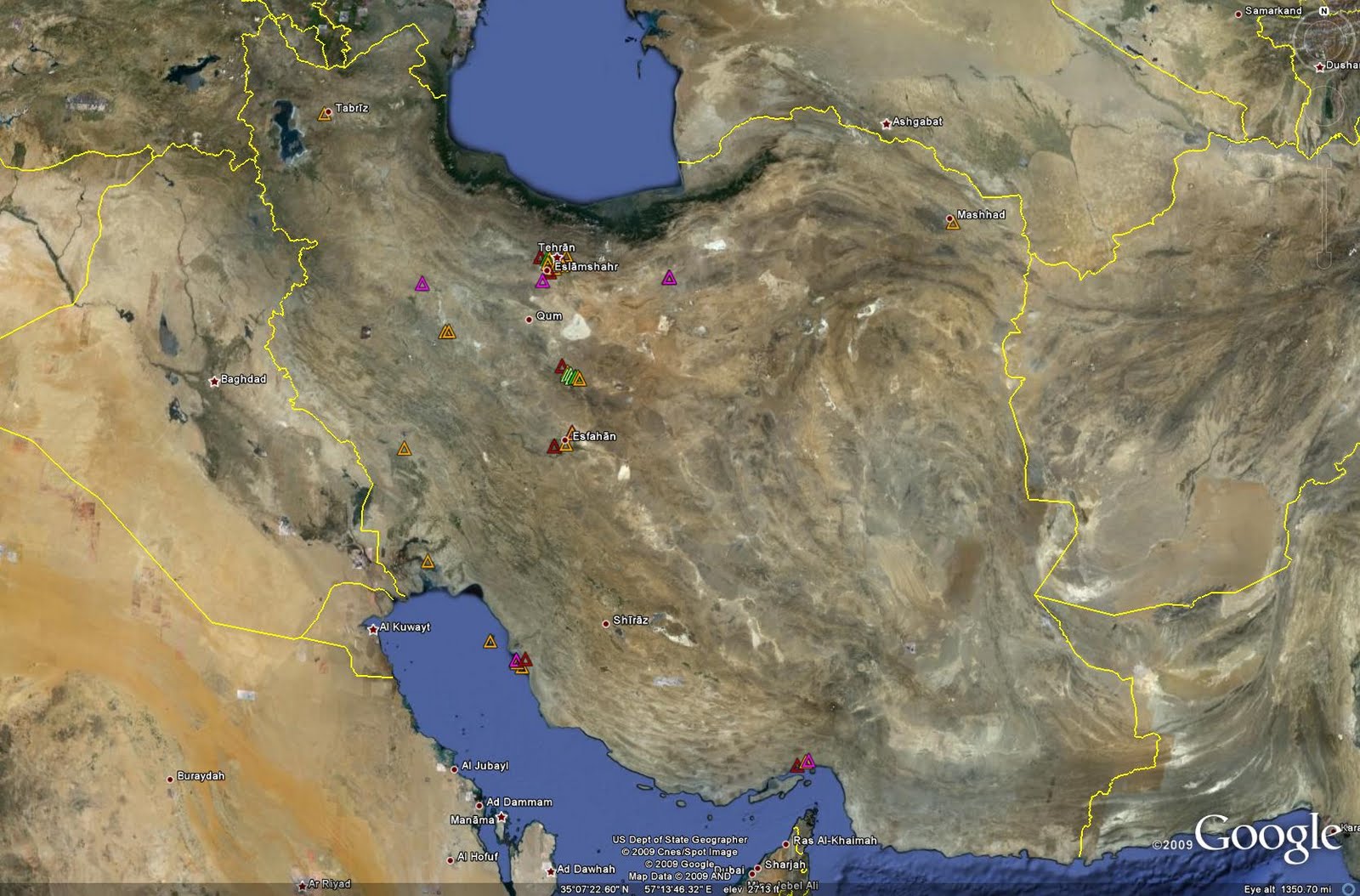

Iran's Strategic SAM ForceThe Iranian air defense network relies on a mixture of Soviet and Western SAM systems. This relatively unusual mix stems from both pre- and post-1979 acquisitions from the West and the Soviet Union, respectively. The following SAM systems are currently in service as part of the overall air defense network: HQ-2 (CSA-1 GUIDELINE, a Chinese-produced S-75 derivative, employing the GIN SLING engagement radar), MIM-23 HAWK, S-200 (SA-5 GAMMON), 2K12 (SA-6 GAINFUL), and Tor-M1E (SA-15 GAUNTLET). Early Warning / Surveillance CoveragePrimary early warning and target track generation for the Iranian strategic SAM force is handled by a network of 24 EW radar sites, one of which is currently inactive. These sites are primarily situated along the periphery of the nation, with additional facilities located in the vicinity of Arak and Esfahan. A third of the facilities are located along Iran's strategically important Persian Gulf coastline. The following image depicts the location of Early Warning radar sites in Iran: |

SAM CoverageCurrently, there are 41 active SAM sites inside Iran. The following image depicts the locations of these sites. HQ-2 sites are red, HAWK sites are orange, S-200 sites are purple, 2K12 sites are bright green, and Tor-M1E sites are faded green. The following image depicts the overall SAM coverage provided by Iranian air defense sites. Using the same color scheme applied in the previous image, HQ-2 sites are red, HAWK sites are orange, S-200 sites are purple, 2K12 sites are bright green, and Tor-M1E sites are faded green. |

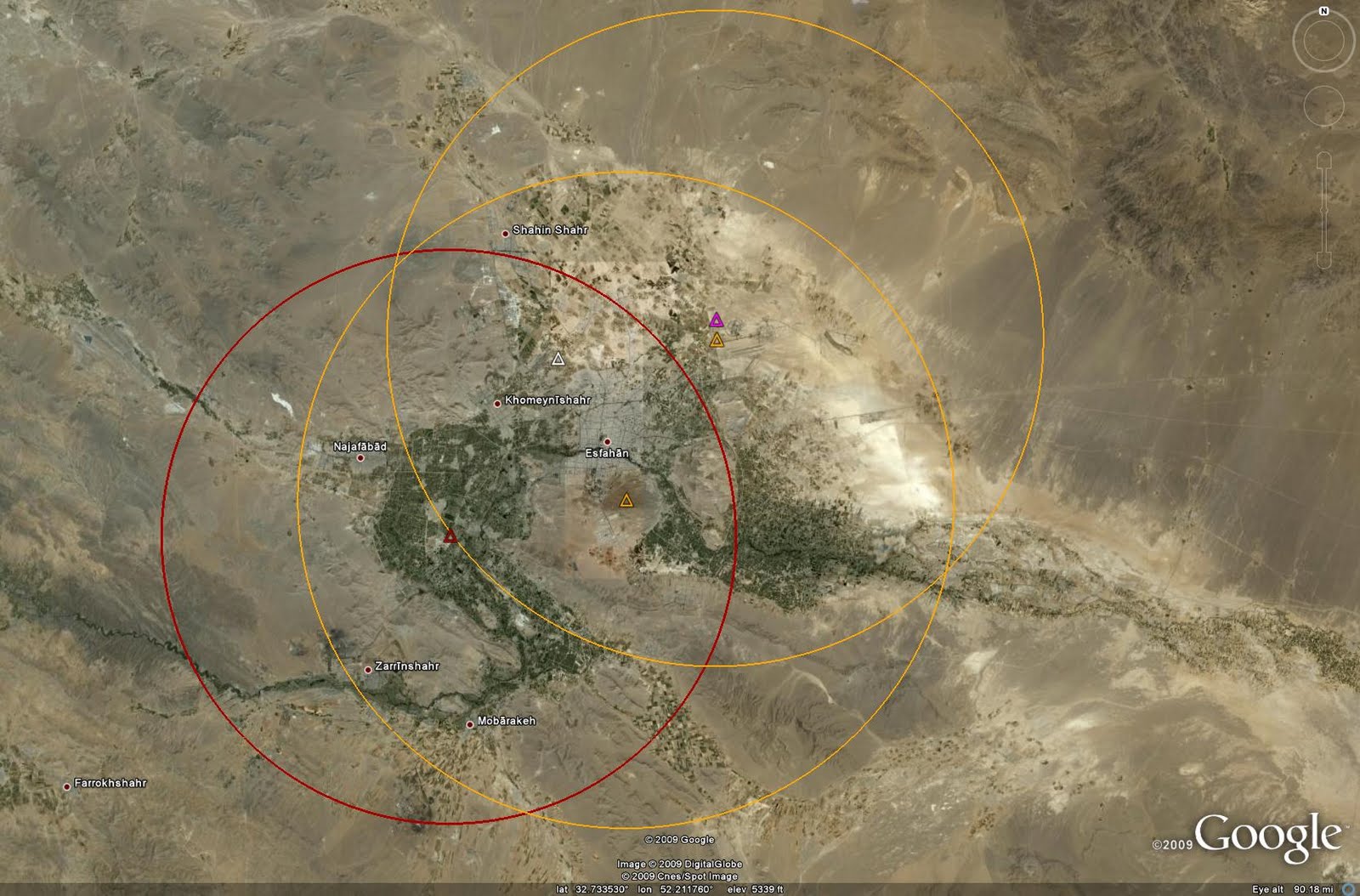

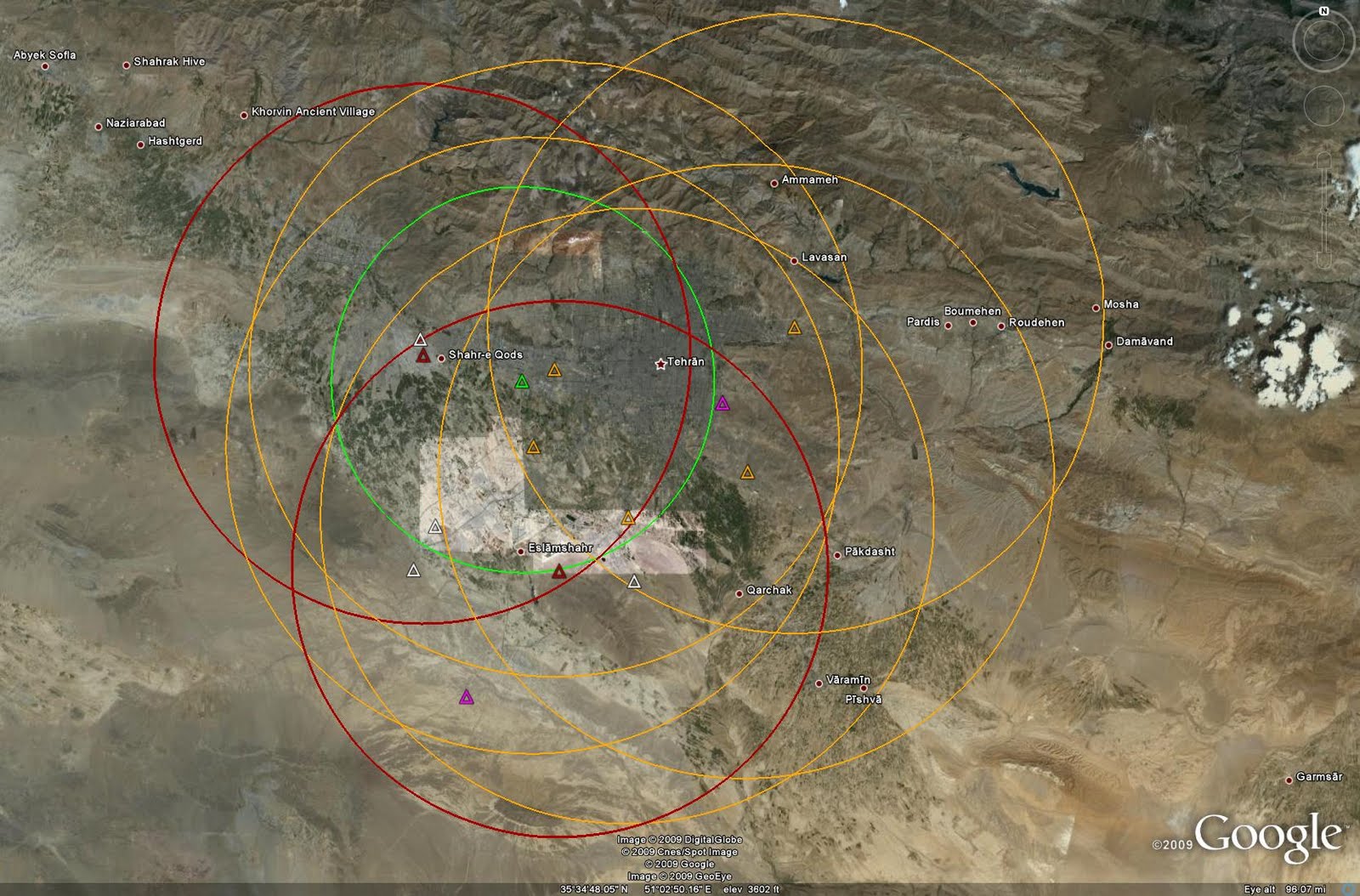

Strategic SAM Force CapabilityNational S-200 CoverageThe primary means of air defense in Iran, insofar as SAM systems are concerned, is the deployment of 7 S-200 firing batteries throughout the nation. The four northernmost sites are positioned to defend the northern border and the region surrounding the capital of Tehran. A fifth site is situated to defend facilities in and around Esfahan in central Iran, including the Natanz nuclear facility. The last two sites are situated at Bandar Abbas and Bushehr and provide coverage over the Straits of Hormuz and the northern half of the Persian Gulf, respectively. The northern four S-200 sites, as well as the southern two sites, are well positioned to provide air defense outside Iran's borders to deter any inbound aggressor from approaching the ADIZ. The central site near Esfahan is a curiosity, however. The southern and western portions of the coverage area are limited due to the presence of a good deal of mountainous terrain, in some cases 10,000 feet or more higher than the terrain where Esfahan is located. This also affects the remaining six sites, but they are affected to a lesser degree due to the fact that they are positioned to defend outwards towards the border and beyond, not likely intended to defend against targets operating deep within Iranian airspace. The Esfahan site, in direct contrast, is apparently situated to defend a central portion of the nation, and as such is limited in its effectiveness by the aforementioned terrain considerations. The curiosity lies in positioning a long-range SAM system in such a fashion to apparently intentionally limit its effectiveness. This can be overlooked to a small degree as the S-200 is not necessarily a preferred system when it comes to engaging low-altitude targets, but the terrain in the area would seem to greatly reduce the effectiveness of the Esfahan site. The radar horizon is the key issue here, as each piece of terrain situated higher than the engagement radar will carve a significant portion out of the system's field of view and limit its ability to provide widespread coverage. The Warsaw Pact practice of installing the 5N62 SQUARE PAIR engagement radar on large elevated concrete platforms was an expensive attempt to overcome this limitation. Iranian S-200 sites appear to be intentionally limited in their composition. Each site consists, unusually, of one 5N62 SQUARE PAIR engagement radar and two launch rails. For more information on this unusual practice, reference the following article on this site: S-200 SAM Site Analysis . Point DefenseThe remainder of Iran's SAM sites are positioned in a point defense arrangement scheme to provide coverage of key areas in the nation. There are five key areas defended by shorter-range systems: Tehran, Esfahan, Natanz, Bushehr, and Bandar Abbas. All of these areas are also covered by S-200 sites, which are co-located in some instances, providing a degree of overlapping coverage in these locations. The capital city of Tehran is defended by five HAWK sites, two HQ-2 batteries, and a 2K12 battery. There are four empty sites in the area. The southwestern two sites are prepared HQ-2 sites, while the northwest and southeast sites are prepared HAWK sites. Were the empty sites to be occupied, they would form an inner HAWK barrier and an outer HQ-2 barrier oriented to defend against threats from the west and south. This layout may be a legacy leftover from the Iran-Iraq War. Two S-200 sites are also in the vicinity, and the other two S-200 sites to the east and west also provide limited coverage of the capital. The following image depicts SAM coverage of Tehran:  There

are two HAWK sites and one HQ-2 site in the vicinity of Esfahan. One of

the HAWK sites, as well as the S-200 site in the area, are located on

the grounds of Esfahan AB, with the HAWK site likely situated to

provide point defense of the airbase. The HQ-2 site and the remaining

HAWK site are located south of Esfahan proper. An empty HAWK site is

also located in Esfahan, likely representing a dispersal site for the

battery at Esfahan AB.

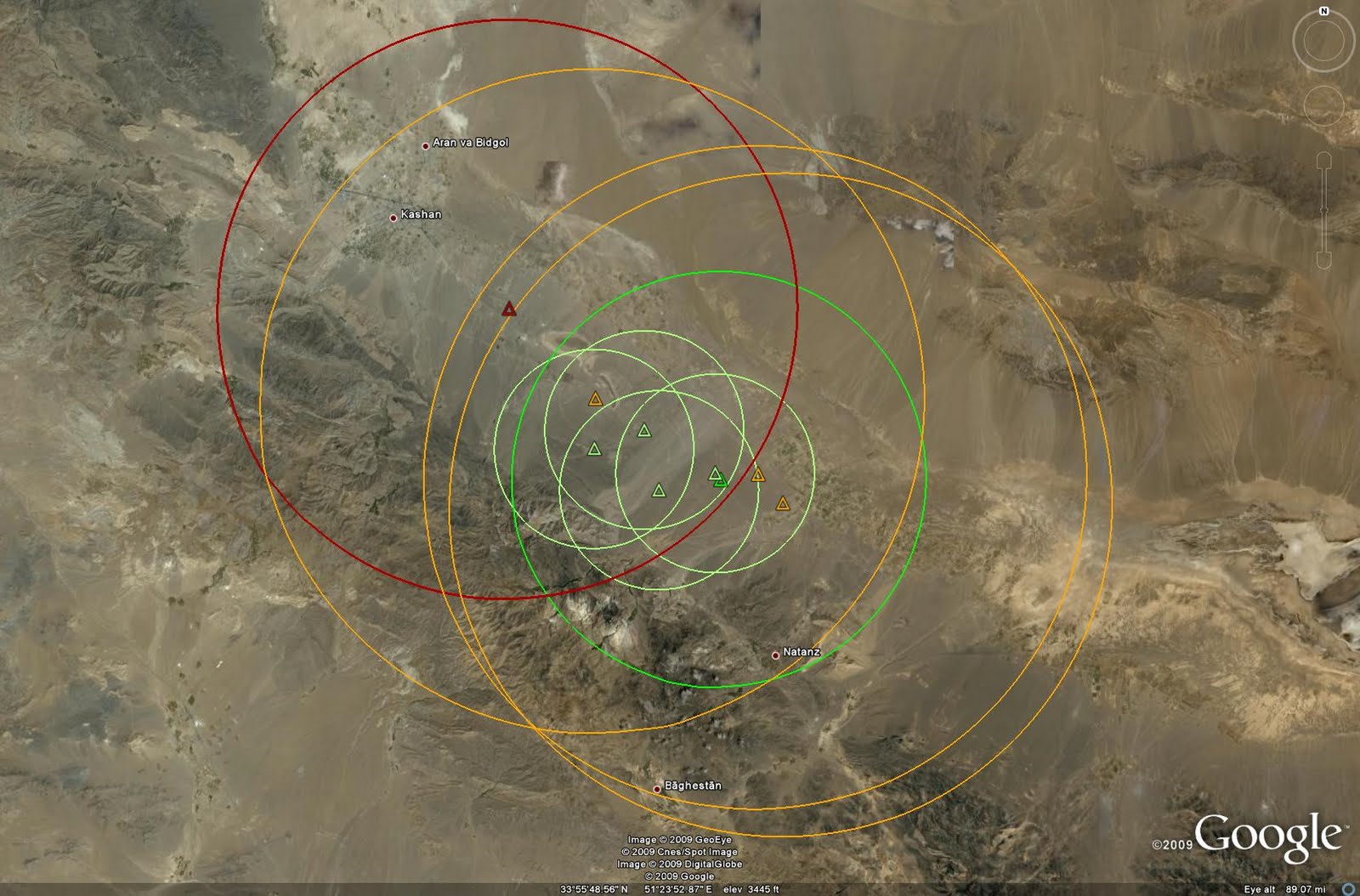

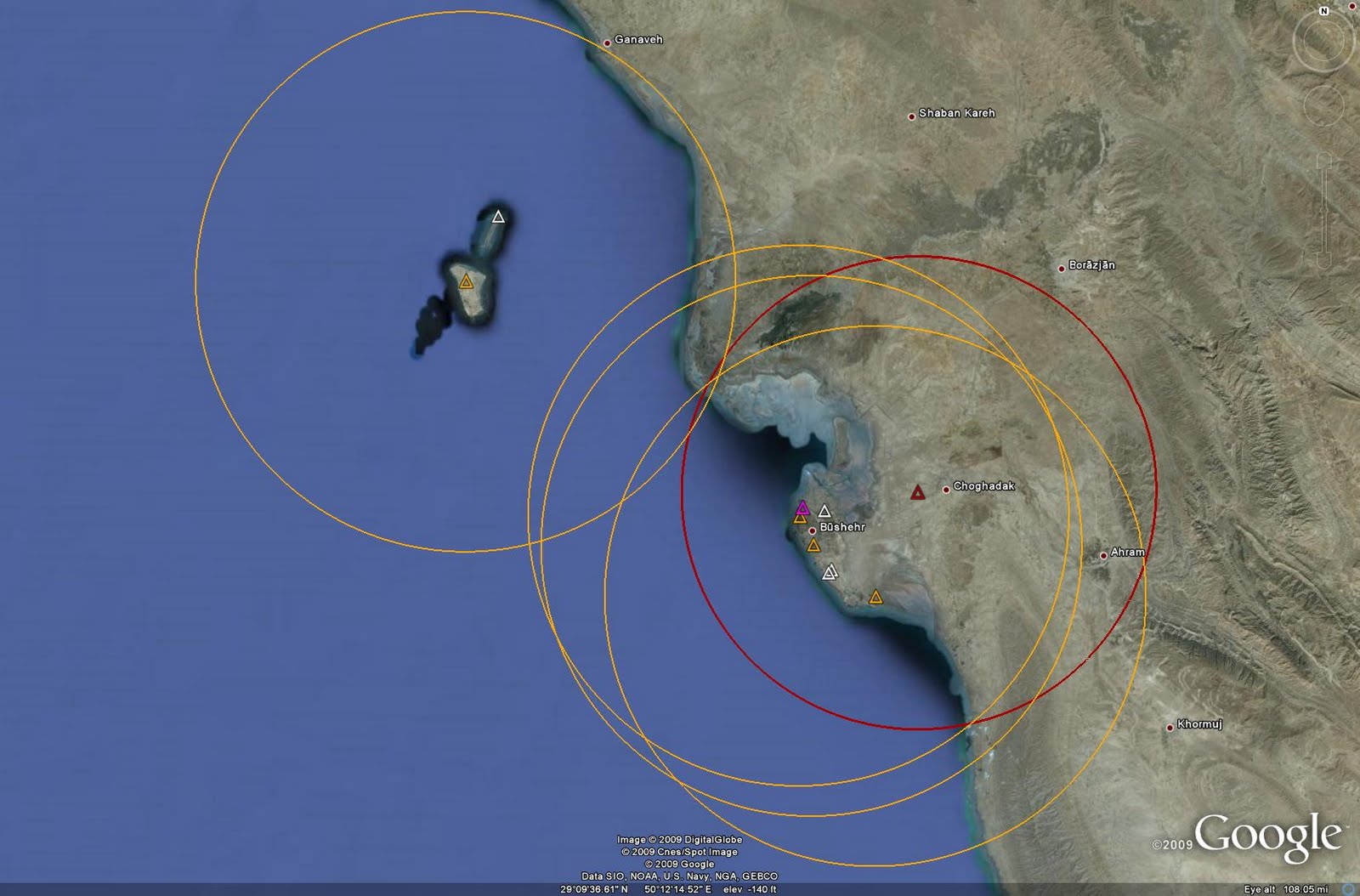

The following image depicts SAM coverage in the vicinity of Esfahan: Nuclear related facilities near Natanz are afforded a layered defense by recently-deployed tactical and strategic SAM ssytems. Natanz is defended by one HQ-2 site, three HAWK sites, one 2K12 battery, and four Tor-M1E TELARs. The tactical systems were deployed between September 2006 and September 2009; the increased air defense posture may signify an increase in activity at the nuclear facility. The following image depicts SAM coverage in the vicinity of Natanz: The Bushehr region, which contains a key nuclear facility, is defended by four HAWK sites and an HQ-2 battery. Two HAWK sites are located on the grounds of the Bushehr military complex, with a third site being located offshore on Khark Island, while the HQ-2 battery is located further inland from the military complex nearer to Choghadak. Bushehr AB is also home to an S-200 battery. There are three unoccupied HQ-2 sites and a single unoccupied HAWK site in the area as well. Three unoccupied sites are situated around the nuclear complex, perhaps suggesting that any weapons-related work has been moved from the facility to one of the various inland nuclear research and development locations such as Natanz. This would appear to be a sensible course of action given the serious vulnerability of the coastal Bushehr nuclear facility to enemy activity approaching from the Persian Gulf region. The remaining unoccupied HQ-2 site is located on an islet northeast of Khark island. The following image depicts SAM coverage in the vicinity of Bushehr: Bandar Abbas, home to most of the Iranian Navy fleet, including the deadly Kilo SSK fleet, is defended by one HQ-2 battery and one HAWK battery. There is an S-200 site in the region as well. The following image depicts SAM coverage of Bandar Abbas: The S-200 sites located in the vicinity of both Bushehr and Bandar Abbas provide Iran with a significant air defense capability over not only a good portion of the Persian Gulf, but also over the critical Straits of Hormuz. This SAM coverage, which can be further expanded thanks to the presence of unoccupied, prepared HAWK sites on the islands of Abu Musa and Lavan, allows Iran to provide increased air defense in conjunction with fighter aircraft to protect any naval operations in the region, including the potentially catastrophic mining of the Straits of Hormuz. |

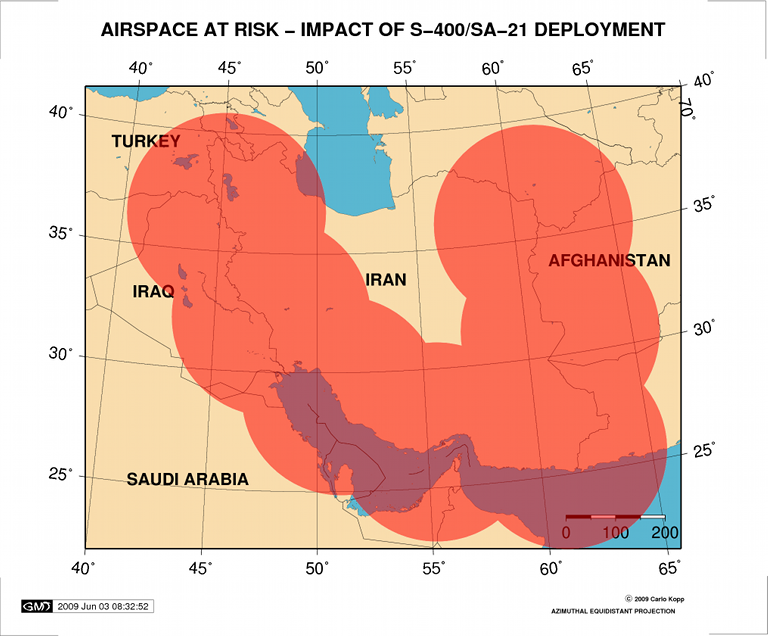

Air Defense IssuesThe problem with Iran's strategic SAM deployment is the evident over-reliance on the S-200 system to provide air defense over most of the nation. The S-200 is certainly a threat to ISR aircraft such as the U-2R or E-3, but the primary threat which Iran must consider is that of standoff cruise missiles and strike aircraft featuring comprehensive EW suites. Against these types of low-RCS or maneuverable targets, the S-200 cannot be counted upon to be effective. Libyan S-200 systems proved completely ineffective against USN and USAFE strike aircraft in 1986, and the Iranian S-200s would logically be expected to fare no better in a much more challenging contemporary air combat environment. As stated previously, the remainder of the SAM assets are primarily situated to provide point or local area defense and as such do not represent a serious threat to a dedicated and sophisticated enemy. Even lesser-equipped nations would be able to explot the various gaps and vulnerabilities in the coverage zones, provided the S-200s could be neutralized in some fashion, be it through ECM, technical capability, or direct attack. This raises the question of the importance of SAM systems to Iran's overall air defense network. Given the current deployment strategy, the small number of sites, and the capability of the systems themselves, it is likely that Iran places more importance on the fighter force as an air defense element. This would explain the continued efforts to retain an operational fleet of F-14A Tomcat interceptors. The short range of the HQ-2 and HAWK systems, coupled with the inability of the S-200 to effectively deal with low-RCS targets, also explains well documented Iranian attempts to purchase advanced SAM systems from Russia and China. It is possible that Iran simply does not feel that a robust SAM network is necessary. Given the aforementioned terrain constraints in some areas of the nation, as well as the lack of a large number of what may be regarded by the Iranian government as potentially critical targets inside Iran, the Persian nation may have simply taken a minimalist posture, relying on the S-200 for long-range defense and the other systems as point defense weapons to defend Iran's critical military and political infrastructure. Another reason for the lack of deployed SAM systems could be that the shorter-ranged HQ-2 and HAWK systems are no longer viewed as being effective enough to warrant widespread use. HQ-2 sites are currently 33% occupied, with HAWK sites being approximately 50% occupied, perhaps signifying more faith in the HAWK system but still demonstrating a potential overall trend of perceived un-reliability. Iran does have reason to suspect the reliability of the HAWK SAM system against a Western opponent, as the missile was an American product and has been in widespread use throughout the West for decades. The HQ-2, however, should be regarded as potentially more reliable, as it is not a standard (and widely exploited) S-75 but rather a Chinese-produced weapon with which the West should have a lesser degree of technical familiarity insofar as electronic counter-countermeasures performance, if not kinematic performance, is concerned. A high ratio of unoccupied sites could be due to financial reasons (lack of operating funds may have resulted in a number of batteries placed in storage) or simple attrition (they may have been expended or destroyed in the Iran-Iraq War), of course, but those facets of the equation cannot be examined through imagery analysis alone. It should be mentioned that one possible source of attrition for the HQ-2 system is the conversion of many missiles to Tondar-69 SSMs to complement CSS-8 SSMs (HQ-2 derivatives) obtained from China. Many batteries may also be out of service for modification to Sayyad-1 standard, which represents a modification of the HQ-2 design with some indigenous components. ConclusionSuperficially, Iran's ground-based air defense picture appears to be relatively robust thanks to the presence and reach of the seven S-200 batteries. However, a closer analysis reveals an overall coverage which is currently full of holes and vulnerabilities that a potential aggressor could exploit. The Iranian strategic SAM force is clearly in need of a serious upgrade, one which is more substantial than simply producing modified HQ-2 missiles. The presence of air interceptors and numerous terrain constraints do explain away some of the negative aspects of Iran's SAM network, but taken as a whole it represents a relatively ineffective form of defense against a modern agressor. Given the current political climate, it would be in the best interest s of the Iranian military to proceed with a widespread upgrade, with the most effective option being the purchase of S-300PMU-2 or S-400 SAM systems for Russia, or perhaps the more cost-effective and similarly capable HQ-9 SAM system from China. Incorporating either purchase into a package deal with modern fighter aircraft such as the Su-30MK or J-10 would result in a much more robust air defense capability. |

Impact of S-300PMU1 / S-400 Deployment |

|

|

References

|

|

|

|

|

Imagery Sources: Internet sources. |

|

Technical Report APA-TR-2010-0102 |

|

|||||||||||||

![Sukhoi PAK-FA and Flanker Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/flanker.png) |

![F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/jsf.png) |

![Weapons Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/weps.png) |

![News and Media Related Material Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/media.png) |

||||||||||

![Surface to Air Missile Systems / Integrated Air Defence Systems Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/sams-iads.png) |

![Ballistic Missiles and Missile Defence Page [Click for more ...]](APA/msls-bmd.png) |

![Air Power and National Military Strategy Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/strategy.png) |

![Military Aviation Historical Topics Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/history.png)

|

![Information Warfare / Operations and Electronic Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/iw.png) |

![Systems and Basic Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/technology.png) |

![Related Links Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/links.png) |

|||||||

![Homepage of Australia's First Online Journal Covering Air Power Issues (ISSN 1832-2433) [Click for more ...]](APA/apa-analyses.png) |

|||||||||||||

| Artwork, graphic design, layout and text © 2004 - 2014 Carlo Kopp; Text © 2004 - 2014 Peter Goon; All rights reserved. Recommended browsers. Contact webmaster. Site navigation hints. Current hot topics. | |||||||||||||

|

Site Update

Status:

$Revision: 1.753 $

Site History: Notices

and

Updates / NLA Pandora Archive

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

Tweet | Follow @APA_Updates | |||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

![F-111 Aardvark Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/f-111.png)

![F/A-18 Hornet and Super Hornet Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/fa-18a.png)

![Aerial Refuelling and Airlift Capabilities Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/aar-lift.png)

![Directed Energy Weapons and Electromagnetic Bombs Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/dew.png)

![Notices and Updates Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/notices-128.png)

![APA NOTAM and Media Release Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/notams-128.png)

![APA Research Activities and Policy / Technical Reports Index [Click for more ...]](APA/research-128.png)

![Search Air Power Australia Website [Click for more ...]](APA/search-128.png)

![Briefings and Submissions - Air Power Australia [Click for more ...]](APA/briefs-128.png)

![Air Power Australia Contacts [Click for more ...]](APA/contacts-128.png)

![Funding Air Power Australia [Click for more ...]](APA/funding-258.png)