|

||||||||||||||||||||||

![Home - Air Power Australia Website [Click for more ...]](APA/APA-Title-Main.png) |

||||||||||||||||||||||

![Sukhoi PAK-FA and Flanker Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/flanker.png) |

![F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/jsf.png) |

![Weapons Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/weps.png) |

![News and Media Related Material Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/media.png) |

|||||||||||||||||||

![Surface to Air Missile Systems / Integrated Air Defence Systems Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/sams-iads.png) |

![Ballistic Missiles and Missile Defence Page [Click for more ...]](APA/msls-bmd.png) |

![Air Power and National Military Strategy Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/strategy.png) |

![Military Aviation Historical Topics Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/history.png)

|

![Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance and Network Centric Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/isr-ncw.png) |

![Information Warfare / Operations and Electronic Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/iw.png) |

![Systems and Basic Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/technology.png) |

![Related Links Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/links.png) |

|||||||||||||||

![Homepage of Australia's First Online Journal Covering Air Power Issues (ISSN 1832-2433) [Click for more ...]](APA/apa-analyses.png) |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Last Updated: Mon Jan 27 11:18:09 UTC 2014 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

![Home - Air Power Australia Website [Click for more ...]](APA/APA-Title-Main.png) |

||||||||||||||||||||||

![Sukhoi PAK-FA and Flanker Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/flanker.png) |

![F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/jsf.png) |

![Weapons Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/weps.png) |

![News and Media Related Material Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/media.png) |

|||||||||||||||||||

![Surface to Air Missile Systems / Integrated Air Defence Systems Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/sams-iads.png) |

![Ballistic Missiles and Missile Defence Page [Click for more ...]](APA/msls-bmd.png) |

![Air Power and National Military Strategy Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/strategy.png) |

![Military Aviation Historical Topics Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/history.png)

|

![Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance and Network Centric Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/isr-ncw.png) |

![Information Warfare / Operations and Electronic Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/iw.png) |

![Systems and Basic Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/technology.png) |

![Related Links Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/links.png) |

|||||||||||||||

![Homepage of Australia's First Online Journal Covering Air Power Issues (ISSN 1832-2433) [Click for more ...]](APA/apa-analyses.png) |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Last Updated: Mon Jan 27 11:18:09 UTC 2014 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sea Control - Submarines or Air Power? | ||

First published in Australian Aviation July, 1996 by Carlo Kopp |

||

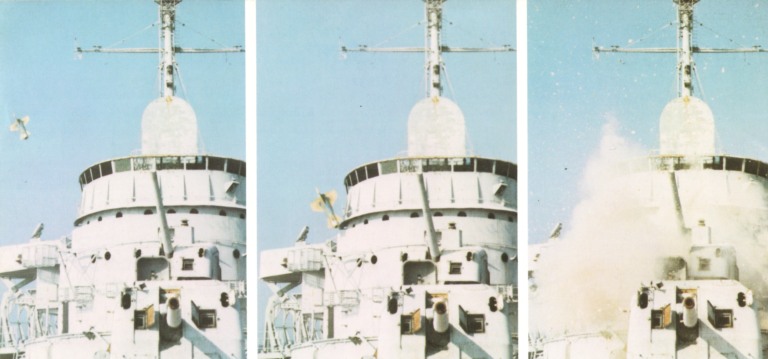

Rockwell GBU-15 CWW glidebomb impacts a warship target during trials. Widely exported EO guided weapons such as the Russian KAB-500Kr and KAB-1500Kr/TK would produce similar effects to equivalent US guided bombs (US Air Force image). |

||

|

Air power has been the decisive factor in nearly every major naval engagement since the beginning of the Second World War. Whether used by the Allies or the Axis Powers, air power when systematically applied to naval warfare annihilated naval surface forces and transport convoys not defended by friendly aircraft. Some important examples bear examination. The battle of the Atlantic initially favoured Germany, and the Luftwaffe's Focke Wulf Condors wreaked havoc upon Allied shipping convoys on the high seas until countered by escort carriers and fighters. The infamous story of convoy PQ-17, largely sunk by the Ju-88s and He-111s of the Luftwaffe, has been told many times. When the Allies gained the ascendancy in the Atlantic, it was again land based air power which played the decisive role. Coastal Command's Liberators, Catalinas and Sunderlands blocaded Germany and hunted down most of the Kriegsmarine's U-boat fleet. Mosquitos and Beaufighters cut the shipping lanes in the North Sea. The battle of the Mediterranean was dominated by air power, initially the Stukas and He-111s of the Luftwaffe. Later RAF and USAAF aircraft cut Rommel's lifeline to North Africa, seeing to the demise of the Afrika Korps (1). Closer to home, the US-Australian executed Battle of the Bismarck Sea saw a major Japanese invasion convoy annihilated off the coast of New Guinea (2). This came less than two years after the Japanese Imperial Navy's land based torpedo and dive bombers sank the Repulse and Prince of Wales off the Malaysian coast. What is little known, is that Curtis LeMay's B-29 force in the Marianas, whilst bombing Japan's cities to rubble, also conducted a major minelaying campaign against Japan's ports and coastal shipping lanes. The B-29s, on the basis of statistics published by the US Navy, sank more shipping through minelaying than the much vaunted USN submarine arm did (3). Whether we examine Luftwaffe performance in the Artic, or USAAF performance off the Japanese coast, published statistics from many sources clearly indicate that land based aircraft sunk more shipping than either the U-boats or the US Navy's submarines did, at a fraction of the operating costs and loss rates of the latter. Whether shipping was destroyed by direct attack or mining, aircraft did so far more efficiently. More recently, RAF and RN Harriers and Sea Harriers played a decisive role in the retaking of the Falklands, and Argentina's only useful opposition was provided by the Fuerza Aerea Argentina (AAF), which sank four destroyers and frigates, and an important heavy container ship using by modern standards a marginal capability (a handful of Exocets and WW2 vintage USAAF dumb bombs). Were Argentine bombs fused properly, the losses would have been at least twice as great (4). US Navy operations against Iran in the late eighties saw the Iranian Navy annihilated when faced by Harpoon firing A-6 bombers, while the heaviest US casualty of the period was an FFG-7 which was nearly sunk by an accidently targeted Iraqi air launched Exocet. During the Gulf War, USN and RAF aircraft annihilated Iraq's naval capability in a matter of days, using Harpoons, rockets, cannon and bombs. The Iraqi Navy suffered the maritime equivalent of Khafji, their greatest contribution to the war being the decorating of Allied aircraft with appropriate stencils. No less than 138 vessels were destroyed or severely damaged, nearly all by Allied air power. The US surface fleet nearly lost two ships to Iraqi naval mines. The historical evidence is irrefutable. Aircraft are a vastly greater threat to shipping and warships than submarines and surface warships are, moreover the latter are also highly vulnerable to air attack. What is the Primary Role of a Navy?The primary role of a navy is to control the seas (5). This is accomplished by engaging shipping by direct attack and by mining, or the threat of doing so. The ascendancy of the submarine and aircraft carrier during WW2, and the preeminent role performed by these classes of vessel continue to this very day. The battleship, and conventional surface combatants in general, have declined in importance since 1939. The primary role of the surface combatant today is to provide a measure of air defence, defend other vessels from submarines, and support amphibious landings with gunfire. The evolution of the modern anti-shipping missile has led to a situation where shipping must be defended from hostile missile firing aircraft at significant ranges, pushing up the size and weight of carrier based fighters to the point where they can only be effectively deployed on large carriers such as those used by the USN. The composition of a CVBG today is largely defensive, with a single carrier needing to deploy many fighters, multiple AEW aircraft, and be escorted by up to a dozen air defence cruisers (AAW), ASW destroyers and light escorts such as frigates, as well as one or two attack submarines. Such is the value of a carrier to opponent and user alike, that its deployment in contested waters requires significant ASW and AAW support. The lightweight carrier is simply not a viable proposition in contested waters (6). In the context of a navy's primary role of sea control, unless the navy is able to deploy one or more fully capable CVBGs, its primary tool for sea control will be the submarine. The submarine will attack shipping with torpedoes and tube launched anti-shipping missiles, and lay mines. It can also be deployed defensively to engage hostile submarines. Mines are a particularly valuable weapon as they are simple, cheap, reliable and persistent. Clever use of minefields can deny an opponent the use of ports, shipping channels and lanes, as well as force shipping into kill zones patrolled by submarines and aircraft. Modern mines are very difficult to find and remove, and can be easily delivered by naval vessels and aircraft. In a strategic war, sea control is usually employed offensively as a means of blockading an opponent's shipping lanes or ports, or to enable amphibious forces to make a beachhead on a contested coastline. Blockade can often starve an opponent of resources and war material to the point where they are unable to sustain their war effort and collapse as a result - Japan in 1945 is a good example. The ability of any contemporary navy other than the USN to achieve even a degree of sea control in the face of a well equipped modern air force is questionable. Whilst top of the line submarines stand a reasonable chance of evading ASW aircraft, their ability to sustain operations effectively whilst under constant aerial harassment must be questioned. Every engagement with the enemy localises their position and increases their vulnerability to attack. Surface Action Groups (SAG) comprising cruisers, destroyers and frigates will not resist sustained attack by state of the art air forces, which can saturate their SAM and AAA defences with anti-shipping missiles and anti-radiation missiles. Once the SAG loses its area defences (when the AAW cruisers are taken down with ARMs and ASMs), then they will be picked off piecemeal with laser guided bombs and ASMs. The SAG is not survivable under sustained and concentrated air attack, moreover attacking jets can usually stand-off from outside area defence SAM range and keep lobbing ASMs at the SAG until its air defences collapse. The ability of a SAG to provide useful defence of convoys is

also open to questioning. A repeat of the PQ-17 fiasco, or the Bismarck

Sea battle would be the most likely outcome. Only the US CG-47 Aegis

class cruiser has any chance of usefully defending a convoy. If the air

attack is sustained and concentrated, once the cruiser has exhausted

its

magazines the battle is lost.

The Collins class

submarine

represents the state of the art in conventional attack submarine

capabilities. Due its slow transit time and limited payload, it is an

inferior sea control asset to tanker supported tactical jets. The

submarine can however play a vital role in supporting air strikes, by

driving shipping into kill zones, mopping up stragglers, carrying out

Bomb Damage Assessment and by providing Combat Search and Rescue if

needed.

The F/RF-111C strike aircraft can attack shipping with Harpoons, Have Naps, Laser Guided Bombs, as well as lay naval mines. This asset provides the RAAF with a tremendous capability to perform the sea control mission, but requires tanker support to fully exploit its potential.

For the cost of a single additional Collins submarine, the ADF could acquire a squadron of KC-135R tankers which would allow the F-111 Wing to conduct sea control operations to greater radii than that of the submarine force, as well as make all F-111G aircraft Harpoon capable.

Sea Control and the ADFThe RAN is clearly aware of these circumstances, the building of six Collins class submarines and recent lobbying for an additional two reflect a focus on using the submarine, armed with Harpoons, torpedoes and mines, as its primary tool for sea control (recent reports indicate the external mine carriage facility on the Collins will not be used, and mines are thus to be carried at the expense of torpedoes and Harpoons). The RAN's surface fleet, comprising in the early part of the next century a mix of lightweight FFG-7 and ANZAC frigates, is simply not survivable without the support of RAAF fighters and AEW&C aircraft. Since survivable and thus large carriers are simply beyond our means as a nation, this situation will not change. The question which we must then ask is whether a force of six to eight submarines can do a better job of performing the vital sea control mission, than could be performed by the RAAF using its AP-3C, F-111 and F/A-18 wings. Several issues should be considered in these circumstances:

Flexibility favours air power, as aircraft can deploy at hundreds of knots while submarines deploy at tens of knots. Submarines must return to base to refuel and rearm, or rendezvous with submarine tenders, in either instance having to do so from outside the coverage of hostile maritime aircraft. Aircraft can be reloaded much faster than submarines, and can engage ships, submarines and other aircraft. Whilst a submarine can dominate only the surface and subsurface medium under favourable circumstances, aircraft can dominate the air, surface and subsurface media. An AP-3C can engage shipping and submarines, while the F-111 and F/A-18 can engage aircraft and surface vessels. All types can lay naval mines (the standard air delivered mine is a parachute retarded Mk.80 series bomb warhead with a Mk.36/40/41 destructor kit attached (7), released at low level). Air power is therefore a more flexible tool than submarines for sea control Weight of fire favours air power, as six or less aircraft can carry an equal load of Harpoons or mines to what a submarine can. A squadron of twelve F-111s or F/A-18s can deliver the weight of fire of two submarines on a single sortie, and several times the weight of fire if we allow the aircraft to fly home, reload and re-engage, which the aircraft can do in much less time than it takes a submarine to break contact, meet with a tender, and redeploy to regain contact with the enemy. As an example, in the time it takes for a sub to transit 1,000 nautical miles at 20 kt to a kill zone, an F-111 can make no less than six trips with a 3 hr allowance for reloading and refuelling on each sortie - in effect a single F-111 delivers about the same aggregate weight of fire as a Collins class sub. Air power therefore delivers much greater weight of fire than a submarine can. Survivability favours air power, as modern tactical jets can deal with hostile fighters, maritime aircraft and surface vessels very effectively. Whereas a submarine must evade hostile ASW aircraft and vessels, and submarines, in order to perform its mission, all of these threats are typically easy targets for aircraft to successfully engage. The maritime patrol aircraft which is a deadly threat to the submarine, is easy meat for an F-111 or F/A-18. The same is true of surface vessels. Whilst a submarine can in theory engage an ASW aircraft with an encapsulated SAM, the submarine is still the hunted party in the engagement. An aircraft can always disengage and retreat much faster from an unfavourable engagement. Statistics from WW2 suggest that submarines suffered much higher loss rates than aircraft in sustained operations. Air power is thus more survivable than submarines are. Coverage favours air power, as an aircraft using its ESM and radar can sweep a much larger area much faster than a submarine using a towed sonar. In the sea control scenario, where surface vessels are the target, aircraft offers substantially better coverage than submarines, moreso if we can deploy several aircraft for each submarine. Costs have and continue to favour air power across all three categories. A Collins class submarine at $500M plus apiece is worth almost the cost of a squadron of state of the art tactical jets, new. Losing a single submarine is a similar loss to that of a whole squadron of tactical fighters, with a greater loss of life. In terms of bang for buck, aircraft are therefore much better value as a sea control asset. Persistance and operating radius favour the submarine, where air power lacks proper inflight refuelling support. Where air power has proper inflight refuelling support, it can match the operating radius of the submarine with no difficulty. The RAF's Nimrod operations during the Falklands campaign are a good example.

This final point brings us to the central issues for the ADF. Is it better to spend a billion dollars on a pair of submarines, or invest less money in strengthening RAAF operating budgets, inflight refuelling capability and the Strike Reconnaissance Wing ? Given the primacy of air power as a sea control tool, should the RAN retain its responsibility and operating budgets as the service primarily tasked with sea control, or should this activity become primarily a RAAF responsibility ? To explore the first issue, let us indulge in some basic arithmetic. The current SRW (82 WG) active complement comprises 22 F/RF-111C and 6 F-111G aircraft for a total of 28 aircraft with nine F-111Gs in reserve. Let us first assume that all aircraft are made Harpoon capable, and all are available for use. With four Harpoons apiece this yields a loadout of 4 x 36 = 144 rounds for 82 WG, which compares favourably with the total load of 6 x 23 = 138 rounds (Harpoon/torpedo) for the Collins force. Assuming that the aircraft can deliver six or more sorties in the time a sub can deliver one sortie, the existing 82 WG inventory has more than six times the potency of the planned submarine force as a ship killing asset. These are interesting numbers. If we rate combat effectiveness by weight of fire alone, the acquisition of one submarine increases our naval sea control combat effectiveness by a factor of one in six (17%), the acquisition of two subs raises this to two in six (33%). On the other hand, the current 22 Harpoon capable F-111s already have more than 400% the combat effectiveness of the planned 6 strong submarine force. Subjecting the 15 F-111Gs to an AUP upgrade to provide a Harpoon capability for all 36 operational airframes increases this ratio beyond 625%. Let us now make some comparisons. A Collins class sub costs about $500M. The cost of an incremental AUP upgrade on the 15 F-111G aircraft has been estimated at between $80M and $100M. This leaves a whole $400M dollar difference. Let us then assume that this money is spent on buying 16 second hand KC-135R tankers, which yields $25M per tanker aircraft. This is a generous allowance per airframe, as the USAF KC-135R cost about US$10M to upgrade with CFM-56 engines from paid off KC-135As delivered prior to 1966, and zero timed before 1980. It would allow for a glass cockpit, an electronic warfare fit and support infrastructure. For the cost of a single submarine the ADF could have not only a fully Harpoon capable 36 strong F-111 Wing, but also a squadron of tankers to provide this Wing with an operating radius equal to or better than that of the submarine force. Not to speak of the other benefits which accrue from having tankers, as I have argued in August issue AA. A single submarine would thus improve the ADF's sea control combat effectiveness by 17%, whereas its cost spent on an F-111G upgrade and 16 tankers would improve the ADF's sea control combat effectiveness by something well in excess of 250% of the potency of the whole submarine force. Let us now assume a revised active wing size of 56 F-111 aircraft, assuming the existing 37 airframes are all made available. This would require the acquisition of an additional 19 F-111 airframes at about $90M for the package. Assuming then $5M per airframe for an AUP upgrade on each and every aircraft amounts to about $95M. For half of the cost of an additional submarine the ADF could double the size of the F-111 Wing, providing twelve times the combat effectiveness of the six strong submarine force. If the reason for acquiring two more submarines is to increase the ADF's capability in the sea control role, we can do far better by spending three quarters of the money on tankers and extra F-111s, and get vastly more capability for the dollars invested. Why bother with more submarines ? The second issue also bears some consideration. The existing arrangement is for the conduct of joint operations between the RAN and the RAAF. What this really means is that the RAAF is a service provider to the RAN, the joint force commander would almost certainly be Navy and the RAN would develop the battle strategy, ostensibly with RAAF advice on operations, and the RAAF would execute it. Considering the previous analysis, we can argue a very strong case for the joint force commander to be RAAF rather than RAN, and for the RAN to be the service provider to the RAAF in sea control operations. The RAN would provide intelligence support and use its submarines to assist the RAAF in its conduct of operations. RAN submarines could drive hostile shipping into kill zones, mop up stragglers after air strikes, provide post strike Bomb Damage Assessment, as well as provide Combat Search And Rescue if needed. This arrangement reflects the weight of respective capabilities far better than the Navy-lead-service-in-sea-control-operations model. The latter is an anachronism.

The government should give careful consideration to how it allocates both capital investment and running costs in maritime surveillance and sea control capabilities. Substantially better bang per buck can be achieved by shifting resources and responsibilities from the RAN to the RAAF.

This discussion has simplified many of the issues, for instance by neglecting the important capabilities of the AP-3C and F/A-18, but the essence would be no different were the analysis much more thorough. Air power is the dominant weapon in strategic naval operations and the ADF's ORBAT, operational running budgets and command and control arrangements should reflect this. To do any less is to place tradition above the realities of modern warfare.

The plight of lightly armed surface warships under sustained air attack is no better illustrated by the Royal Navy's heavy losses during the Falklands campaign. The operationally marginal Argentine Air Force and Naval Air Arm came very close to defeating the UK's armada using visually aimed dumb bombs and a handful of Exocets, delivered by a motley collection of sixties technology Mirages, Daggers, A-4 Skyhawks and Etendards, lacking even basic electronic warfare capability and flying at the limit of their combat radius.

Pic.5 This plot

illustrates the

number of sorties which could be flown by an F-111 during the time a

submarine takes to transit to the kill zone, against the distance to

the

kill zone. The calculation assumes a 3 hour turnaround between sorties,

and an average TAS of 430 kt assuming that the lower speed on climbout

and combat speed of 550 kt average out. Radii beyond 800 nautical miles

require inflight refuelling. Of interest is the fact that a single

tanker supported F-111 can fit up to 9 sorties in at 3300 NMI, allowing

it to deliver 156% greater weight of fire than a submarine can. |

||

References |

||

|

||

|

|||||||||||||

![Sukhoi PAK-FA and Flanker Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/flanker.png) |

![F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/jsf.png) |

![Weapons Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/weps.png) |

![News and Media Related Material Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/media.png) |

||||||||||

![Surface to Air Missile Systems / Integrated Air Defence Systems Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/sams-iads.png) |

![Ballistic Missiles and Missile Defence Page [Click for more ...]](APA/msls-bmd.png) |

![Air Power and National Military Strategy Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/strategy.png) |

![Military Aviation Historical Topics Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/history.png)

|

![Information Warfare / Operations and Electronic Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/iw.png) |

![Systems and Basic Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/technology.png) |

![Related Links Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/links.png) |

|||||||

![Homepage of Australia's First Online Journal Covering Air Power Issues (ISSN 1832-2433) [Click for more ...]](APA/apa-analyses.png) |

|||||||||||||

| Artwork, graphic design, layout and text © 2004 - 2014 Carlo Kopp; Text © 2004 - 2014 Peter Goon; All rights reserved. Recommended browsers. Contact webmaster. Site navigation hints. Current hot topics. | |||||||||||||

|

Site Update

Status:

$Revision: 1.753 $

Site History: Notices

and

Updates / NLA Pandora Archive

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

Tweet | Follow @APA_Updates | |||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||