| Defence

Assertion and APA Response |

Score

|

|

EF

|

NS

|

SP

|

SUPER

HORNET

In keeping with the 2000 Defence

White Paper [Click

for more ...], the ADF is committed to maintaining an edge in

regional

air combat capability. |

1

|

|

1

|

Maintaining an edge in regional air combat capability requires the

maintenance and acquisition of combat aircraft, weapons and systems

which have a decisive edge over regional capabilities. Neither the

Super Hornet nor the Joint Strike Fighter provide an edge over late

production Sukhoi

Flanker variants, or late production S-300PMU/S-400

series Surface Air Missile systems, all of which are proliferating

rapidly in Asia.

As long as both the Government and Defence remain committed to the

Super

Hornet and Joint

Strike Fighter, they cannot be committed to maintaining an edge in regional

air combat capability. They are exposing us, Australia

and future generations of Australians to significant risk.

|

|

|

|

| The

Super Hornet is the best aircraft to meet Australia’s bridging air

combat requirements as we prepare for a JSF-based future, subject to

government decision. |

1

|

1

|

1

|

As there is no need for premature

retirement of the F-111, there is no need for a “bridging air

combat requirement” and thus the Super Hornet. Considering the fighter

types currently in production, the F-22A

Raptor presents a far better choice in all key roles, compared to

the Super Hornet.

The claim of a “JSF-based future” presupposes that the next government

will agree to purchase the JSF despite its unsuitability for our

strategic needs.

|

|

|

|

| The

Super Hornet is a battle-proven, multi-role aircraft that is

clearly the only capable, available system which meets Defence’s

requirements in the next 8-10 years. |

3

|

1

|

1

|

To date the Super Hornet has not been flown in combat against a modern

Integrated Air Defence System (IADS), or against modern “double digit”

Surface to Air Missile systems, or later generation Flanker

fighters.

It has been flown only in very low threat environments against

disorganised legacy technology Surface-to-Air threats, and used

to bomb

low threat conventional targets, insurgents and terrorists. The most

prominent “combat experience” the Super Hornet has is against an enemy

who buried

their air force under sand dunes.

The Super Hornet cannot be regarded to be “multirole” in the classical

sense of the term, as it lacks the performance to be credible in air

superiority and air defence roles, and it lacks the survivability to be

credible in strike roles against well defended targets.

Australia's provable strategic needs “in the next 8-10 years” cannot be

met by the Super Hornet, “Classic” Hornet or any other low performance

aircraft in this class. All are performance constrained to being

sub-sonic machines with low supersonic dash capabilities when combat

loaded. The JSF will be in this very same class – its design

specifications and the ubiquitous Cost As an Independent Variable

(CAIV) have made it so.

|

|

|

|

|

The Super Hornet is the clear choice as a bridging air

combat capability for three reasons:

- First because of its excellent

capability to meet Australia’s requirements;

- Second because of its availability

and supportability; and

- Third because Air Force has the

capacity to make this transition more easily than with any other

aircraft.

|

3

|

1

|

|

- First the Super Hornet cannot meet

Australia's developing strategic needs due to its poor

aerodynamic and stealth performance;

- Second other fighter types

including the F-22A

Raptor could be acquired in the timeframe of interest but the

Government and Defence have yet to formally

ask; supportability of the Super Hornet will present issues since

it shares little commonality with the RAAF's 'Classic' Hornets;

- Third the transition effort, given

the different airframe and systems of the Super Hornet compared to the

'Classic' Hornet, will be as much if not more than a new aircraft type

(e.g. F-22A Raptor) with considerably greater risk of maintenance,

configuration control and logistical errors and mistakes; and

- Fourth to overcome the latter, the

Defence bureaucrats’ solution is to ‘de-risk the program’ by handing

all these activities plus engineering control of sovereign assets into

the hands of non-Australians in overseas companies. The reason

for this ‘de-risking’ is a lack of confidence in our own abilities – “the great Australian cultural cringe”

– which, in turn, will lead to loss of jobs and the further

‘de-skilling’ of Defence, itself, and, more significantly, Australian

Industry.

|

|

|

|

| The

Super Hornet is in service with the United States Navy through to

2030 and will continue to be upgraded, keeping it relevant through

until 2020. |

|

1

|

1

|

US strategists are already deeply concerned about the viability of the

Super

Hornet in the 'Sukhoi-rich' Asia-Pacific region over the coming decade.

Its limitations cannot be fixed by upgrades as they are inherent in the

shaping and airframe design of the aircraft.

|

|

|

|

| It

will ensure our air combat capability edge is maintained through the

transition to F-35 over the next decade. |

1

|

1

|

1

|

The aerodynamic and stealth performance limitations of both the Super

Hornet and the F-35 will deny an ‘air combat capability edge’ should

either of these types enter RAAF service.

|

|

|

|

| The

Block II Super Hornet will be on the ground in Australia in a

little over two years. |

|

|

1

|

Whether the aircraft is delivered or not in this timeframe, full

operational capability will not be achieved in anything

approaching that timeframe.

|

|

|

|

| The

Super Hornet acquisition will allow us to retire the F-111 at a

time of our choosing. |

|

|

1

|

The Defence bureaucracy decided to prematurely retire the F-111 in

2003, with an intended retirement date of 2010. The ‘time of our

choosing’ was a flawed decision taken four years ago by those in the

ranks of the senior Defence bureaucrats and ministerial advisers

in Canberra, then

entrusted to guard the

nation’s air combat capability edge, an edge that had been protected

and honed since the end of

the Korean War. The repercussions of that ‘imposed’ edict is

now readily apparent for those who have the capacity to put bias to one

side

and view the issues dispassionately and objectively.

|

|

|

|

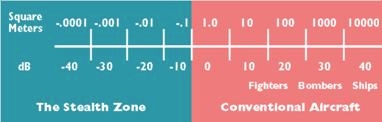

Regarding

claims the Super Hornet is not sufficiently stealthy

The Super Hornet is a low-observable (LO) aircraft, orders of magnitude

more 'stealthy' than F-111 or Su-30s.

|

2

|

|

1

|

This claim ignores the reality that the Super Hornet must carry

external fuel tanks and weapons to be useful in combat. The radar

signature of these external stores largely nullifies any signature

reduction achieved in the Super Hornet by the use of the trapezoidal

inlets, sculpted inlet tunnels, and radar bay shroud.

The Russian

Irbis E radar carried by late model Flankers will detect a 1 square

metre target at 160 NMI (~300 km), yet the centimetric band radar

signature of

even a single external store such as a missile rail or fuel tank is of

that order of magnitude.

The claim that the Super Hornet is “orders of magnitude more ‘stealthy’

than F-111 or Su-30s.” suggests the Super Hornet has a radar cross

section of the order of 0.1 square metres or better, a courageous claim

given the shaping design limitations of the Super Hornet.

Source: Iris Independent

Research

Source: Iris Independent

Research

|

|

|

|

| The

F-35 JSF is a Very Low Observable (VLO) aircraft and true 5th

generation. |

2

|

|

|

The non exportable US

only F-35 JSF variant may be able to achieve true Very Low Observable

(VLO) performance only

in a narrow sector around its nose, but the aircraft cannot be termed

low observable in the tail and beam sectors by any stretch of the

imagination. Therefore the JSF is at best a Low-Observable (LO)

aircraft with single sector Very Low Observable (VLO) performance.

Export models are expected to have inferior stealth performance

compared to the non exportable US only F-35 JSF variants.

A ‘true 5th generation’ fighter will incorporate supersonic

cruise, high agility, all aspect stealth and integrated avionics.

The JSF has only one of these attributes (integrated avionics) and part

of another (all aspect stealth), therefore it cannot be a ‘true 5th

generation’ fighter like the F-22A Raptor or the Russian PAK-FA

(T-50) when it comes into service circa 2015.

|

|

|

|

|

Regarding Super Hornet not being 5th generation

The ADF has never said that the Super Hornet is '5th generation' - a

term referring to the combination of stealth and sensor integration.

The only two true 5th generation aircraft are F-22

Raptor and the F-35 JSF.

|

1

|

|

1

|

No, but Boeing St Louis does make the claim that “the Super Hornet

really is a fifth generation air plane” in their promotional video, an

extract of which was shown on the 4 Corners Program.

It remains to be determined exactly where the Minister found the

information upon which he made his “no brainer decision”, and exactly

where senior Defence officials found their information on the Super

Hornet aircraft.

The F-35 JSF cannot be a ‘true 5th generation’ fighter as it will never

have supersonic cruise, high agility, and all aspect stealth

capabilities.

|

|

|

|

Super

Hornet vs Su-30 series aircraft

If a Super

Hornet was to meet a Su-30 in the coming 8 years, ADF pilots would want

to be in the F-18F cockpit every time. Any pilot who has flown the new

Block II F-18F with AESA radar would feel the same way. |

|

|

2

|

Success in combat is determined by advantages in capability, numbers

and the ability to exploit these advantages operationally. The feelings

of pilots have much less impact, as proven repeatedly in air wars since

1914.

Sir Robert

Brooke-Popham observed in 1942, days before many brave young RAAF

pilots were killed in combat with superior Japanese A6M2 Zeroes, that “[Brewster] Buffaloes are quite

enough for Malaya”,

and that the A6M2 Zero was “on a par with

our Buffalo ...”.

|

|

|

|

| The

Super Hornet is a true multi-role aircraft that spans the air

combat spectrum, including maritime strike, which is so vital for

Australia. |

2

|

|

|

The performance limitations of the Super Hornet render the first claim

erroneous.

While the Super Hornet has the capability to carry maritime strike

weapons like the subsonic Harpoon, its range performance is inadequate

for this role without significant aerial refuelling support, unlike the

F-111.

Su-30 variants arriving in the region are much superior in the maritime

role, with better range/payload performance than the Super Hornet, and

the ability to carry far more potent anti-shipping missiles like the

supersonic Yakhont

and Moskit

(Sunburn).

|

|

|

|

| The

Block II airframe is redesigned for signature reduction and the

aircraft is built around the most advanced radar in any non-fifth

generation aircraft in the world. |

|

|

2

|

While the Super Hornet airframe does have some signature reduction

measures, as noted previously, the signature of external weapons and

fuel tanks will be enough to render the aircraft highly vulnerable to

long range engagement using advanced Russian radars and missiles.

While the APG-79 radar in the Block II Super Hornet does use

newer transmitter and packaging technology than the Russian Irbis E

radar in the Su-35BM/Su-35-1

[NB zipped 20 MB PDF],

it still uses similar receiver and

processor technology.

More importantly, it has only one half the antenna size and less peak

power compared to the Russian radar. As a result the Russian Irbis E

radar will outrange the APG-79 in the Block II Super Hornet.

|

|

|

|

|

Modern lethal weapons render any aircraft performance

measure

irrelevant if it does not enable first shot. First shot is achieved

long range through:

- modern networking;

- survivability

– (through signature reduction and integrated electronic

counter-measures that deny opponents the ability to shoot);

- advanced radars to cue weapons early; and

- lethal missiles – (with long range and protection

against countermeasures).

|

|

|

4

|

In most realistic scenarios, the late model Sukhoi Flanker will achieve

a long range first shot capability against the Super Hornet, through:

Moreover, aircraft aerodynamic performance

measures are not irrelevant if these allow a fighter to rapidly escape

from an opponent's missile engagement envelope. The poor supersonic

performance of the Super Hornet denies it such opportunities.

|

|

|

|

| In

its air superiority roles, the F/A-18F possesses all these attributes

and will test any modern air defence system. |

1

|

2

|

|

The late variants of the Sukhoi Flanker also possess all these

attributes, but are also much more agile and much faster than the Super

Hornet, giving the advantage in combat to the Sukhoi.

Moreover, these attributes will have little bearing on the ability of

the Super Hornet to survive in “any modern air defence system”, where

the regional benchmark are the S-300PMU-2/S-400

and S-300VM long range

Surface to Air Missile systems. US strategists regard only the F-22A

Raptor and B-2A

Spirit to be capable of surviving encounters with these

Russian air defence weapons.

|

|

|

|

|

Air combat capability is about far more than the

aircraft

specifications. Reliable, sustainable logistics support, the best

training and a full air combat system of command and control is

required to match modern threats.

|

|

|

2

|

More importantly, and unfortunately, turnkey support provided by

Russian contractors,

including aircrew and groundcrew, allow regional Flanker operators to

also achieve “reliable, sustainable logistics support, the best

training and a full air combat system of command and control”.

|

|

|

|

| No

other aircraft can meet this requirement in the bridging timeframe

better than F-18F Super Hornet. |

1

|

|

|

Australia's strategic needs could be met far better in this timeframe

by the F-22A Raptor.

|

|

|

|

Was

DSTO’s F-111 wing testing flawed?

There were

no errors in the set-up of DSTO’s F-111C wing fatigue test. The wing

fatigue test was developed to simulate the loads on the aircraft

in-flight. |

2

|

1

|

2

|

There were a number of significant errors in the set-up of DSTO’s

F-111C wing fatigue test. Primarily, these were due to the

re-direction, to other non-F-111 related projects, of the funds that

had been appropriated by Government in 1998 to the F-111 Sole Operator

Programme, as recommended by the RAAF F-111 Support Study of 1996. The

resulting significant shortfall in funding led to serious shortcomings

in the test set up as well as the testing itself including, inter alia, inadequate pre-test

inspection of the test wing; inadequate instrumentation for monitoring

the whole of the wing during testing; a test rig that introduced

non-representative loads into the wing; and, insufficient resources to

adequately monitor and analyse the whole wing structure during testing

to ensure any defects that developed during testing were detected as

early as possible.

Basically, the DSTO had barely sufficient funding to focus on the inner

wing area (the wing root, including the Wing Pivot Fitting) let alone

the whole of the wing, including the outer wing panels where the “surprise, catastrophic failure” was

to occur.

A simple comparison between this test programme and the approach,

methodologies and test techniques used on the F-A-18 International

Follow-On Structural Test (IFOST) Programme done with the Canadians

highlights the deficiencies that led to the “surprise, catastrophic failure”

experienced on the first wing test article in the DSTO F-111C Wing

Fatigue Test Programme.

|

|

|

|

| The

F-111C wing fatigue test was initiated by Air Force and conducted

by DSTO to manage and address fatigue cracking problems identified in

the mid-1990s. |

1

|

1

|

1

|

The F-111C wing fatigue test was initiated by the engineering experts

in Air Force and conducted by the experts in the DSTO who were,

unfortunately, subsequently underfunded for doing the work by the

non-experts in Air Force – those whom the Chief of the Air Force and

Chief Defence Scientist referred to in evidence to the Parliamentary

Committee inquiring into air superiority as those who “don’t know what

they don’t know”.

Claiming “to manage and address

fatigue cracking problems identified in the mid-1990s” amounts

to spin, and is indicative of the level of deskilling that has occurred

in Defence, as much as the dominance in the belief of ‘form over

substance’ at the senior levels in both Defence and Government.

Such testing is standard practice in the engineering management of high

performance machines like the F-111. Those who did the F-111

Support Study understood this fact back in 1996, as the extract

below from the September 1996 Addendum to that study

acknowledges. This testing was meant to be routine and part of

the overall risk management efforts which, if done properly, would see

the aircraft remaining operational out to 2020 and, if necessary,

beyond.

|

|

|

|

The

Wing Fatigue test article failed unexpectedly

during testing.

All F-111C wings were subsequently replaced with later model wings

which passed the wing fatigue test.

|

2

|

1

|

2

|

To have a Wing Fatigue test article fail “unexpectedly” during testing was

unheard of in the recent annals of aircraft life extension fatigue

testing,

until this “surprise, catastrophic

failure”. To have such a failure in such testing shows

this first test was non-representative, and thus flawed.

Such testing is all about loading the full scale test article – in this

case an F-111C wing – with representative flight loads and then,

through monitoring and regular inspections, detecting any defect that

may develop and doing so as early as possible.

The process, as was

applied on the IFOST and on all other such testing known to APA, is

then to analyse the defect, develop an ‘in the field’ inspection and

repair which are then sent to the fleet to be applied in the normal

course of maintenance of the aircraft. In the meantime, the test

article is repaired and testing continued until, at such time when the

aims of the testing have been achieved or this overall process reaches

the limit of economic sustainability (whichever comes first), no

further repairs are done and the test article is allowed (and

predictably so) to catastrophically fail.

The test article is then full inspected and analysed.

The first test wing was an ex-RAAF wing that had seen 5,418 hours in

service. The defect that led to this “surprise catastrophic

failure’ of the first test wing was there on day one of the test and

remained undetected throughout the following 8,089 hours of

testing. Over that time, it developed and grew, undetected, into

a crack of the critical size necessary for failure of the

structure. There were other defects in this wing that similarly

developed and grew, undetected, over the 8,089 hours of testing but had

not reached critical size before this “surprise,

catastrophic failure”.

As a result of this

“surprise, catastrophic failure”,

the engineering experts in the RAAF, the DSTO and, importantly,

Industry worked

collegiately and devised automated ‘safety by inspection’

procedures and processes, repair techniques, and an F-111 Wing

Re-furbishment/Repair Line at RAAF Base Amberley through which the

F-111 wings,

both the original wing sets purchased as spares well before the “surprise, catastrophic failure” and

those ‘F’ and ‘D’ Model additional wing sets purchased

following the test failure, have been processed.

To say “All F-111C wings were subsequently replaced with later model

wings which passed the wing fatigue test” is simply untrue and reflects

an incorrect understanding of what has actually been achieved. In fact,

the

F-111s were returned to service with ‘F’ and ‘D’ Model

wings, all of which have now been inspected for defects in the the

areas of

interest, including those found to have gone undetected during the

first failed

test.

When the APA Team last checked, following the retirement out of service

of the

last F-111G aircraft, no cracks had been found in any of the areas on

the wing

where cracks had been allowed to develop and grow either during the

first

failed test or the recent successfully progressing second wing fatigue

test,

prior to that test being shut down. All F-111C aircraft were flying

with the

later, better production quality ‘F’ and ‘D’ Model

wings processed through the F-111 Wing Re-furbishment/Repair Line.

However,

since it is so easy to change the wings on the F-111 and the RAAF now

have so

many spare wings, this may not be the case today, assuming the RAAF are

mitigating risk by processing the F-111 wings through the Wing

Re-furbishment/Repair Line.

As for “...later model wings which

passed the wing fatigue test”, this statement is, simply,

nonsense.

There has been one additional wing fatigue test by the DSTO on a single

wing. This test had surpassed the predicted life of the previous

failed wing test – “….the total

equivalent flight hours at failure was set at 18,918 hours” – by

a significant degree and was exceeding expectations when, following the

Minister’s announcement that he was buying Super Hornets because the

decision “was a no brainer” and “we are hornet country”, the test

program was shut down.

|

|

|

|

Defence

evaluation of various capability options:

It is a normal part of prudent military planning to develop fallback

options for Government consideration. |

1

|

1

|

1

|

At face value, this statement could almost be true though, when

assessed against the norms of complex project management standards and

standard risk management let alone the requirements of the Financial

Management and Administration Act (FMA Act), the Commonwealth

Procurement Guidelines (CPG), the Defence Procurement Policy Manual

(DPPM), and the Defence Capability Life Cycle Management

Guide (DCLCMG) that were applicable at the time of the JSF

decision, the term “a normal part of prudent military planning” should

be changed to “an essential and mandatory part….”.

One would be hard pressed to say that the often used term of “...keeping a watching brief on other

capabilities” satisfies the criteria of “a normal part…” let alone “an essential and mandatory part of prudent

military planning”.

|

|

|

|

|

The bridging capability option leveraged off several

years of on-going analysis through Air 6000.

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

The data and the facts on the public record show that if any such

analysis were done, which might support the decision for Australia to

acquire the Super Hornet, then it was and still is, at best, less than

objective, if not very seriously flawed.

|

|

|

|

|

Preliminary DSTO studies were carried out on both the

technical risk

and operational analysis of Block II Super Hornet as a bridging air

combat capability prior to Government decision.

|

1

|

|

|

The data and the facts, given the documented history of events, when

considered against the statements made by Defence prior to the

announcement of the Government decision, and when compared with the

public assertions of the Minister for Defence, the Hon Dr Brendan

Nelson, in announcing his decision, do not support this claim.

|

|

| The

F/A-18F Block II Super Hornet is clearly the most capable aircraft

across all air combat roles that Air Force have the capacity to

introduce in the bridging timeframe. |

1

|

1

|

|

That Air Force capacity should be a principal determinant for a less

than capable aircraft to be acquired to fill Australia’s air combat

needs is not supported by historical fact or the experiences of those

who have been involved in the introduction of completely new types of

aircraft into Australian service, either in the military or civil

sectors of Australian aviation. Even a cursory look at the

introduction of the C-130, Mirage, F-4E, F-111 and F/A-18A/B into

Australian service shows this statement to be non-sequitur.

The question remains whether any professional with first hand

experience in the introduction, at the level of engineering and

logistical responsibility, of a new complex aircraft type (military or

civilian) into service

in Australia had any accountable input into the planning and any advice

that led to this decision by the Minister.

|

|

|

|

| The

option of the F/A-18F Super Hornet builds on our understanding of

the current F/A-18 fleet. This option is least risk to ensure that

Australia’s capability edge is maintained at a time of major equipment

renewal and change for Air Force |

2

|

|

1

|

Given the unique airframe design, largely different avionics and very

different engines in the Super Hornet, compared to Australia's legacy

Hornet fleet, very little 'understanding of

the current F/A-18 fleet' will be useful in operating the Super Hornet.

Introduction of the Super Hornet will introduce significant strategic

risk as regional Sukhoi operators will appreciate its well known

capability limitations.

|

|

|

|

F-111

The F-111 is a great strike aircraft, professionally operated and

maintained by RAAF personnel. |

1

|

|

|

APA concurs with the statement that the “F-111 is a great strike

aircraft, professionally operated”. However, the Deeper Level

Maintenance of the F-111 fleet is provided by members of the Australian

Defence Aerospace Industry employed by or under contract with Boeing

Australia Ltd or directly with Defence.

|

|

|

|

| The

F-111 has been the stalwart of Australia's air strike power for

last 30 years but will not continue to meet Australia's strategic needs. |

1

|

1

|

1

|

Australia's emerging strategic needs now include:

- Long range strike against land targets

- Long range maritime strike

- Cruise missile defence

- Long range interception of bomber and maritime

aircraft

- Persistent strike against battlefield targets.

- Precision strike against deeply buried targets.

- Full spectrum persistent electronic attack.

In all of these roles an F-111 with suitable technology insertion

upgrades outperforms the Super Hornet decisively, and does so at a

fraction of the cost, with much less or no demand for aerial refuelling

support.

Moreover, neither the Super Hornet nor the JSF can lift deep bunker

busting weapons such as the 5,000 lb class EGBU/GBU-28/B, as both

aircraft are too small, whereas the F-111 is already cleared for these

critically important weapons.

In the vital full spectrum electronic attack role, an EF-111A equipped

with the ALQ-99 ICAP III suite is both more survivable, longer ranging

and more persistent than any other alternative.

|

|

|

|

|

Australia aims to retire the F-111 at a time of our

choosing, noting

the F-111 was planned to retire well before Super Hornet was considered

as a bridging capability.

|

|

|

|

The Boeing St Louis plan to sell Super Hornets to Australia (Project

ARCHANGEL) has been in play since 1998. In 2003, Defence was

directed by the then Minister for Defence, the Hon Senator Robert Hill,

to effectively ‘cease and desist’ from considering an interim fighter

solution.

In 2004, the Chief of the Air Force (CAF) stated that the F-111 would

not be retired until all major capability projects supporting the RAAF

Air Combat Capability were completed and in service. These projects

included the AEW&C aircraft, the New Air Refuel Tankers, the Hornet

Upgrade (HUG) Program, and the Weapons Improvement Programs.

On page 147 of the Defence Annual Report (DAR) published at the end of

calendar year 2004, the following statement may be found:

“The decision to retire

the F111 aircraft around 2010 was announced during the year. To ensure

the maintenance of strike capability, the Government announced that

retirement of the F111 was dependent on the successful introduction

into service of airborne early warning and control and A330 tanker

aircraft, completion of the F/A18 upgrade, and the introduction of

improved weapons and long-range stand-off weapons for P3 Orion and

F/A18 Hornet aircraft.”

In 2005 and 2006, the Chief of Defence Force (CDF), the new CAF, the

Deputy Chief of the Air Force (DCAF), the NACC Program Office and the

Office of the Minister for Defence repeated this statement though

without any reference to arming the P-3 Orion with long range stand-off

weapons notable by its absence.

|

|

|

|

| The

F-111 would operate at increasing operational risk with emerging

threats in the coming decade beyond 2010. It would also operate at

increasing safety risk beyond 2010 with the ageing airframe issues

highlighted by wing fatigue, well publicized fuel tank issues and

wiring looms. |

2

|

2

|

2

|

The operational risk incurred by an F-111 armed with planned cruise

missiles such as the AGM-158 JASSM is very low due to the 150 nautical

mile standoff range of this missile, and even greater range of the

proposed JASSM-ER when carried.

In engagement scenarios involving Surface to Air Missile systems, the

higher speed and much lower penetration altitude of the F-111 compared

to the Super Hornet results in far fewer firing opportunities for a

defending Surface to Air Missile system, especially if a stand-off

weapon is carried by the F-111.

In engagement scenarios involving hostile fighter aircraft, the much

higher speed and persistence of the F-111 compared to the Super Hornet

result in fewer firing opportunities for hostile fighters. A Sukhoi

Flanker cannot run down an F-111 in a tailchase engagement, but it can

easily run down a Super Hornet (or JSF).

The supposed “ageing aircraft issues

highlighted by wing fatigue” have already been addressed.

However, the dominant

factor in the ‘age’ of an aircraft and ‘Aging Aircraft Programs’ is

flying hours and related cycles of operation – not calendar

years. Unlike humans and other ‘biological beings’ from which

people generally derive an understanding of ‘age’ and ‘aging’, properly

maintained aircraft do not ‘age’ or develop ‘ageing aircraft issues’

when they are not flying. After all, they are machines and are

not made of living tissue that ‘ages’ with the passage of time.

As for the “well publicized fuel tank

issues and wiring looms”, this event and the near loss of F-111

A8-112 and crew was a result of sound engineering advice being ignored

by ‘those who don’t know what they

don’t know’ about aviation, in particular the F-111, within

Defence.

In 1999, the fuel tank wiring was identified as one of the high

technical risks on the F-111 fleet by the incoming Deeper Level

Maintenance contractor and members of the Test and Evaluation (T&E)

community in Australia experienced with the F-111. Various

attempts were made in the intervening years by experts in both the RAAF

and Industry to encourage Defence management to fund what was,

ostensibly, an extremely cost effective, low risk replacement program

with later technology fuel tank wiring looms. This contemporary

wiring loom technology had been specifically developed on the back of

lessons learned from fuel tank explosions in other aircraft.

Defence management paid no heed to the advice of these experts.

In 2002, as the statement suggests, the wiring loom induced fuel tank

explosion in A8-112 near Darwin became the “well publicized fuel tank issues and

wiring looms” safety risk.

Footnote:

Defence management has only recently approved funding for replacing the

F-111 fuel tank wiring as first recommended back in 1999, having

finally accepted expert advice that the inspection program implemented

post the explosion in the A8-112 F-1 fuel tank was fundamentally

flawed. These time consuming and quite expensive inspections

could only infer that there were no defects in the wiring looms.

They could not ensure and assure there were none that could develop

into a source for ignition, leading to another fuel tank explosion.

Problems in wiring looms that led to fuel tank explosions in other

aircraft (a.k.a. above ‘lessons learned’ that led to development of the

later fuel tank wiring technology) included well known issues with

Kapton ® insulated wiring. Wiring with this problem insulation

has been fully replaced on the F-111. However, the electrical

looms in Australia’s F/A-18 Hornets are made up of wires with

insulation of this problem type.

|

|

|

|

|

The F-111's effective range is increasingly reduced as

it needs to

avoid air and surface threats rather than having the ability to

penetrate them as can a modern multi-role fighter such as the F-18F

Block II Super Hornet.

|

2

|

|

|

The Super Hornet cannot credibly penetrate integrated air defences

equipped with late variants of the Sukhoi Flanker and

S-300PMU-2/S-400/S-300VM air defence missile systems; in the US force

structure this role is reserved for the F-22A Raptor and B-2A Spirit as

only these types are regarded to be sufficiently survivable.

The Super Hornet will have no choice than to employ “avoidance tactics”

not unlike the F-111, but the lower speed, lower persistence and higher

operating altitude of the Super Hornet will force far more cautious

tactics than feasible with the F-111.

|

|

|

|

| The

F-111 needs a fighter escort with any air threat, is not networked

and doesn't fit into Australia's networked Defence architecture for the

coming decade. |

3

|

1

|

|

The F-111 remains survivable against a wide range of air threats,

especially those lacking the performance to easily gain missile firing

opportunities. Escort is only required against air threats with high

speed, high persistence and high power aperture radar systems, and only

when the F-111 is not carrying a cruise missile warload.

Last year engineers at the RAAF Amberley depot performed prototype

integration of a state of the art MIDS LVT network terminal into the

F-111 avionic system, and did so on a small internal development

budget. The absence of network terminals in the F-111 is because

the Defence bureaucracy refused to fund this low cost enhancement to

capability.

|

|

|

|

The

decision to join the JSF Program

Australia

joined the JSF Program in October 2002 to obtain access to F-35 Air

System information, as well as capability and industry outcomes,

recognising that gaining these benefits did not commit Australia to

acquire the JSF aircraft. |

|

|

1

|

The decision to join the JSF Program was announced in June 2002.

In early 2001, while acting Secretary of Defence, the Undersecretary

of Defence Materiel (USDM), had a meeting at the request and with

the Head of the DMO Aerospace System Division (HASD) and his senior

staff. At this meeting, the USDM expressed his belief that, inter

alia, Defence should ‘go straight for the JSF’ to replace the Hornets

and the F-111s as soon as possible.

Over the intervening 14 months, the USDM and a select group of senior

DMO staff travelled widely; lobbied the Offices of the Ministers for

Defence and Industry; and, ‘recruited’ selected individuals in Defence,

other government departments and Industry to the cause of convincing

others in the Departments of Defence and Industry as well as other key

government departments (e.g. Finance, Treasury and PM&C) that the

Government should ‘decide’ to join the JSF Program.

Clearly, the Capability Staff and the DSTO had no knowledge of these

activities nor the USDM’s intentions since they issued solicitations to

Industry (e.g. AIR6000 Force Mix Option Market Survey etc) in the

latter part of 2001.

If these solicitations had been issued with knowledge of the USDM’s

intentions, then those authorizing the issue of such solicitations

would, inter alia, have been in breach of Commonwealth Procurement

Guidelines (CPG) and its overarching legislations, namely, the

Financial Management and Administration Act (FMA Act).

|

|

| The

decision also recognised the clear benefits that a stealthy,

multi-role, 5th generation JSF offered over the full range of contender

aircraft based on Defence analysis undertaken on contenders to replace

the air combat capability provided by the F-111 and F/A-18 aircraft. |

3

|

|

1

|

The JSF is, at best, a 5th generation aircraft by marketing literature

only. The multi-role and stealthy capabilities of the JSF have yet to

be demonstrated and, rightly, are regarded by most experts as somewhat

problematic at this stage.

The aviation adage of ‘fly before you buy’ has its origins in the

common sense standard of caveat

emptor. Would any of you reading this “On the Record”

statement purchase or commit to purchase an car without at least test

driving it?

At the time of the decision to join the SDD Phase of the JSF Program,

the analysis and evaluation phases of the AIR6000 Project had not yet

been funded, let alone started. Funding approval for this work

under Stage III of Phase 1 of the then AIR6000 Project - the Analysis and Evaluation Stage - was

to be sought in September 2001.

As to what has since then, has any evidence in the form of hard data

and facts or formal reports emerged to support the notion that any

rigorous and objective analysis of the type required by the Defence

Capability Development System that existed at the time of ‘the

decision’ has been done on “the full range of contender aircraft …. to

replace the air combat capability provided by the F-111 and F/A-18

aircraft”?

|

|

|

|

|

For a minimal outlay of only around 0.3% of the JSF’s

development budget, benefits from joining the Program included:

- The opportunity to participate in a developmental

program largely funded by the US Government;

- Privileged access to JSF Program information;

- The opportunity for very detailed technical risk

analysis by Defence of

all JSF systems years before any contractual commitment;

- Constant engagement with the JSF Program Office on

JSF cost analysis.

Unprecedented ability for early development of our concept of

operations and tactics;

- Enhanced opportunities for interoperability and

commonality to support future coalition operations;

- Delivery of the required air combat capability ahead

of non-Partner customers.

The unprecedented opportunity for Australia to participate in, and

influence, the design and capability of an advanced fighter aircraft;

- The opportunity to take part in the JSF test program

(the most comprehensive flight test program ever);

- Australia

is already involved in defining what will be included in the first

upgrades to the aircraft after the current development phase is

complete; and

- The opportunity for Australian industry to be part of

the global supply chain of the world’s largest defence project.

|

1

|

|

1

|

The language used in this statement typifies the flowery marketing

language that has been the hallmark of the AIR6000, now New Air Combat

Capability (NACC) Project, since the announcement of the Government

‘decision’ to join the JSF Program.

However, APA has never criticised this ‘decision’ for the reasons that

were given at the time; namely, for Defence to become a smarter

customer to enable better risk management and informed decision making

while providing Australian Industry access to the world’s largest

defence project. The aircraft's unsuitability for Australia's strategic

environment is an issue in its own right.

APA and many of its colleagues in Defence and Industry see great risks

in the JSF Program which, if appropriately managed collectively, could

be turned into greater opportunities for Australian Industry, Defence

and the JSF Program itself.

Given the multi talented, integrated skills base; expertise in

innovative thinking; and, particular assets able to Test and

Evaluation, that are resident, if not uniquely, in our Nation,

Australians could be helping their American counterparts retire risks

on the JSF Program. This would be complementary to and further

expand opportunities in the already hard won, less developmentally

risky though very important manufacturing and process design work

already being done by members of Australian Industry.

What APA and its colleagues in Industry and Defence are disappointed

with is the lack of foresight, paucity of appropriate risk management

and proper due diligence, and unwillingness to engage in open, critical

debate on the part of the New Air Combat Capability Project Office and

Defence as a whole, while actively trying to suppress independent

thought as well as innovative and countervailing views in Defence and

Industry. These forms of behaviour and their underlying attitude

are a recipe for disaster.

“Fly before you buy”, as the Dutch and British plan to do, should be

the fundamental tenet of the NACC

Project with well considered and developed contingency strategies and

risk treatment plans in place in relation to the capability, cost,

schedule, project risk and Industry issues associated with the project.

|

|

|

|

|

EF |

NS |

SP |

|

Score |

Scoring Totals:

|

Error of Fact - Instances found:

|

42

|

|

|

| Non Sequitur - Instances found: |

|

17

|

|

| Spin

- Instances found: |

|

|

32

|

Totals:

|

42

|

17

|

32

|

![Home - Air Power Australia Website [Click for more ...]](APA/APA-Title-NOTAM.png)

![Sukhoi PAK-FA and Flanker Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/flanker.png)

![F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/jsf.png)

![Weapons Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/weps.png)

![News and Media Related Material Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/media.png)

![Surface to Air Missile Systems / Integrated Air Defence Systems Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/sams-iads.png)

![Ballistic Missiles and Missile Defence Page [Click for more ...]](APA/msls-bmd.png)

![Air Power and National Military Strategy Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/strategy.png)

![Military Aviation Historical Topics Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/history.png)

![Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance and Network Centric Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/isr-ncw.png)

![Information Warfare / Operations and Electronic Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/iw.png)

![Systems and Basic Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/technology.png)

![Related Links Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/links.png)

![Homepage of Australia's First Online Journal Covering Air Power Issues (ISSN 1832-2433) [Click for more ...]](APA/apa-analyses.png)

![Home - Air Power Australia Website [Click for more ...]](APA/APA-Title-NOTAM.png)

![Sukhoi PAK-FA and Flanker Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/flanker.png)

![F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/jsf.png)

![Weapons Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/weps.png)

![News and Media Related Material Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/media.png)

![Surface to Air Missile Systems / Integrated Air Defence Systems Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/sams-iads.png)

![Ballistic Missiles and Missile Defence Page [Click for more ...]](APA/msls-bmd.png)

![Air Power and National Military Strategy Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/strategy.png)

![Military Aviation Historical Topics Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/history.png)

![Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance and Network Centric Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/isr-ncw.png)

![Information Warfare / Operations and Electronic Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/iw.png)

![Systems and Basic Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/technology.png)

![Related Links Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/links.png)

![Homepage of Australia's First Online Journal Covering Air Power Issues (ISSN 1832-2433) [Click for more ...]](APA/apa-analyses.png)

![Sukhoi PAK-FA and Flanker Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/flanker.png)

![F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/jsf.png)

![Weapons Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/weps.png)

![News and Media Related Material Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/media.png)

![Surface to Air Missile Systems / Integrated Air Defence Systems Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/sams-iads.png)

![Ballistic Missiles and Missile Defence Page [Click for more ...]](APA/msls-bmd.png)

![Air Power and National Military Strategy Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/strategy.png)

![Military Aviation Historical Topics Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/history.png)

![Information Warfare / Operations and Electronic Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/iw.png)

![Systems and Basic Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/technology.png)

![Related Links Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/links.png)

![Homepage of Australia's First Online Journal Covering Air Power Issues (ISSN 1832-2433) [Click for more ...]](APA/apa-analyses.png)