|

|

|

|

What are the most common questions

asked about electromagnetic weapons?

Why do they work? The “information age” has

seen the pervasive

use of digital hardware, mostly based on silicon monolithic technology,

across the complete infrastructure of developed nations, whether in

handheld devices, domestic or office equipment, transportation,

production, health, or education. Expose any monolithic semiconductor

device to

voltages, whether transient or radiofrequency, in excess of the

specification limits of several Volts, and bad things usually happen.

Dielectric insulators break down or leak, and reverse biased junctions

suffer avalanche breakdowns. With a mains or battery power supply

attached to the device, often very little energy is actually needed to

initiate a catastrophic electrical failure - the power supply is what

actually delivers the killing blow. Imagine that the electromagnetic

weapon is like a device putting a crack into a dike, and the power

supply is like the body of water which causes the actual damage.

What kinds of electromagnetic weapons exist? Put simply, a

great

many. A trivial taxonomy divides such weapons by steady state or

transient effect, the former being beam weapons and the latter being

one-shot E-bombs, and then by spectral coverage, whether wideband or

narrowband, and low or high frequency, and emitted power. A wideband

low frequency low power one shot weapon might be a submunition for a

cluster bomb using a rare earth magnet with a high explosive jacket,

while a wideband high frequency high power repetively pulsed weapon

might be a Marx bank driven Landecker Ring mounted in the

focal area of

a parabolic dish antenna. The term “E-bomb”, which I coined in 1996,

has

been used to describe high altitude nuclear Electro Magnetic Pulse

(EMP) bombs, as well as much smaller non-nuclear devices based on Flux

Compression Generators, the latter producing direct low frequency

wideband effects, or used as a one-shot pulsed power supply for High

Power Microwave (HPM) tube such as a Virtual Cathode Oscillator

(Vircator).

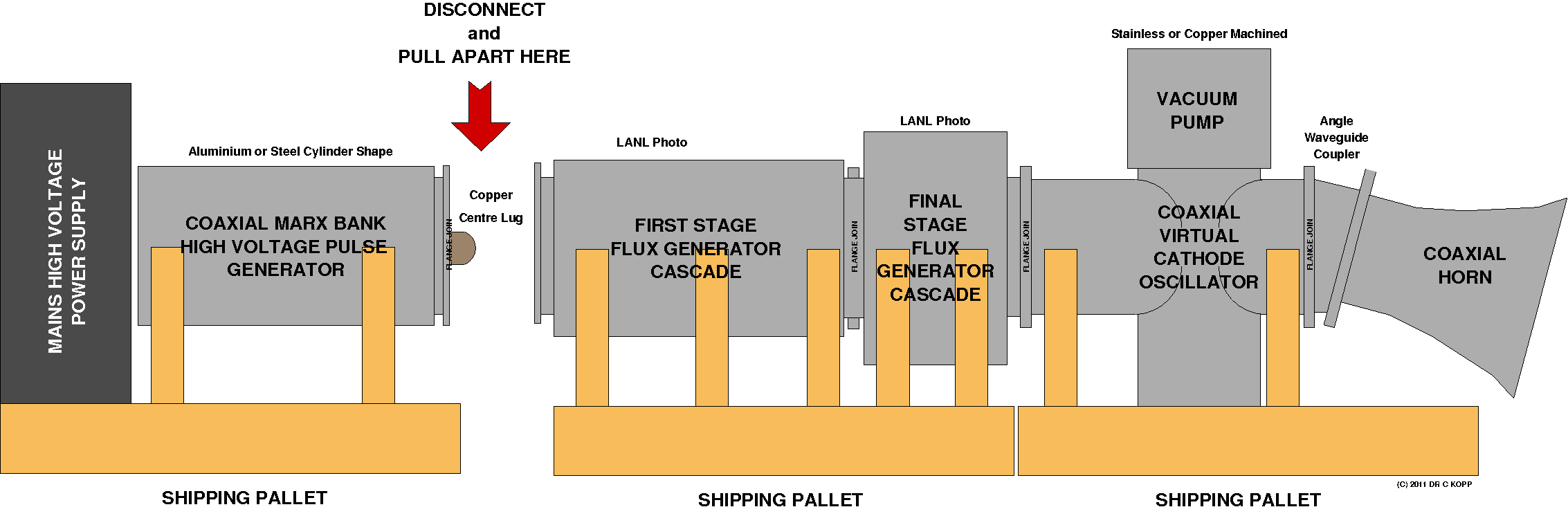

What is a Flux Compression Generator? Invented

by the late Max

Fowler at Los Alamos National Laboratories during the 1940s, the FCG is

an explosively driven

electromagnetic amplifier. Primed with an initial electrical starting current,

a high velocity explosive is used to mechanically compress the magnetic

field, which in turn transfers energy from the explosive into the

magnetic field. While the FCG disintegrates during operation, in

operation it produces an enormously powerful pulse of electrical

current. Cascading two or three FCGs can yield hundredfold amplication

of the initial pulse, which is usually produced by a high voltage

capacitive device

called a Marx Bank. The biggest FCGs have produced peak power

outputs

of many GigaWatts.

Why use a Vircator?

Microwave devices like the Vircator

allow

the power produced by the FCG to be quite precisely focussed against a

target area up to hundreds of metres or more away from the FCG, which

left to itself, produces most damage only within tens of

metres. The antenna attached to the Vircator is not unlike the

reflector in a torch or car headlight. Ordinary inverse square law

physics then apply, with field strength diminishing with distance.

Choose the right E-bomb power, antenna gain, and distance, and you can

achieve a reasonably precise peak electrical field strength over an

intended target area.

How does the microwave power couple into targets?

Place a

digital device into a microwave oven, turn on the oven, and then see if

the device still works. Likely

it won't. Microwave radiation will have penetrated into the device

through cracks, crevices, cooling grills and exposed wiring. Much the

same happens with a microwave E-bomb. Mains power wiring and copper

network cabling will behave like an antenna, and while the E-bomb is

radiating, electrical standing waves will appear on the cables,

producing large voltages at the ends of the cables, where devices are

attached. Gaps, loose panels, cooling grilles and other openings, as

well as antennas, may

also allow the radiation into the equipment. Electrically lethal field

strengths for consumer equipment vary between 10 kiloVolts/metre up to

30 kiloVolts/metre.

What is a cascade failure?

In a large interconnected

system,

like a power grid or computer network, a cascade failure arises when

the failure of one device triggers an overload and failure in another,

and the damage effects then propagate bringing down much, most or all

of the network. E-bombs have the potential to produce massive cascade

failures in a pervasive digital insfrastructure, as they can cause

simultaneous massed failures in a large percentage of electronic

equipment, if not

all electronic equipment, within the lethal

footprint of the weapon. Switchmode

power supplies blowing out can produce electrical spikes in a power

grid, and having hundreds or thousands fail simultaneously across

several square miles of grid can produce damage effects in areas

peripheral to the lethal footprint itself.

How easy are E-bombs to build? Any nation with the technology

to

design and build a nuclear bomb will be capable of designing a

non-nuclear E-bomb, and mass producing it. The main challenge for

entrants into this game is having a sufficient pool of competent

physicists to design devices like FCGs and Vircators. The technology to

construct all of the components in such a bomb would be available in a

1950s university physics lab. With an accurate set of drawings, an FCG

could be constructed in a suburban garage for several hundred dollars

of cost in uncontrolled materials, other than the requirement for

several kilograms of C4, Semtex or other high velocity castable

explosive.

How likely is a terrorist E-bomb attack? How likely is a

tsunami,

volcanic eruption, big solar flare or meteor impact? Given the

pervasive use of highly interconnected digital infrastructure in

developed nations and its resulting vulnerability to such attack, and

the relative simplicity of such weapons technology, the use of such

weapons is ultimately, inevitable. Determining how soon such

weapons will be deployed by terrorists is a trickier proposition, since

they tend to operate in secrecy. Once we see E-bombs deployed by

military forces as standard tactical or strategic weapons, which will

happen through this decade, the odds of a terrorist organisation

acquiring them with or without the consent of the deploying nation go

up enormously. With proven and robust weapon designs in circulation,

terrorists then have the option of reverse engineering them or using

them directly.

How can we protect ourselves from E-bombs? The

simple answer is electro-magnetic

hardening of the infrastructure,

which involves making digital equipment and power supplies "hardened"

to resist high electrical fields, using optical fibres rather than

metallic cables for network connections, and putting protection devices

into antenna feeds and mains power interfaces. There is little point in

this being done by individual home users since having a working

computer without a working network or power grid is not very helpful.

Hardening requires legislation to make it mandatory for all critical

national infrastructure, spanning both government services and

commercial service providers, across all industry sectors. Is this

achievable? As the Y2K experience over a decade ago shows, the answer

is yes. Will it be expensive? That depends on how the problem is

tackled. If equipment is built hardened from the outset, the cost

penalty may be as little as 10-20% of the build cost. Replacing copper

networks with fibre will be costly, but it is also an impending

necessity to get genuinely high data rates across national network

infrastructures, and reduce urban/suburban background noise levels.

If nobody uses an E-bomb against us, is hardening a

waste of time and

money?

This is the perennial question arising with all military technologies.

If you do not deploy it, an enemy will, and will then use it to an

advantage. If you do deploy protective measures, the enemy may be

discouraged or deterred. In the case of electromagnetic hardening,

there are other good reasons for putting it in. Annually insurance

companies pay out considerable funds to compensate subscribers for

electrical damage produced by lightning strikes and main power grid

transient spikes. More importantly, we have observed in recent years

several incidents in which solar weather variations produced

significant mains grid outages over large areas, often with

considerable electrical collateral damage. An unusually powerful event

of this kind hitting the CONUS or EU could produce a major mess, on the

scale of a nuclear EMP attack. Well designed hardening would thus not

only protect against hostile governments, state sponsored terrorists,

and free-lance terrorists, it would also protect against naturally

arising electrical damage effects.

What can I do about overcoming this risk? The

simple

answer is

to write to your local legislator, and do your best to educate them to

the very real risks which unhardened infrastructure presents in an

genuinely electromagnetically hostile environment. The electromagnetic

weapons community has done this over and over again for nearly two

decades, but has frequently not been listened to. Only the United

States has draft legislation, yet to become law, dealing with aspects

of this matter. Until the legislatures across

developed nations understand this is a real risk, and not science

fiction, the necessary legislation will not be produced, and if

produced, will not become law. For better or worse, legislators

in

democracies react primarily to the weight of numbers. Small numbers of

researchers with PhDs will mostly be seen as less important than large

numbers of concerned citizens, especially if the subject matter is

esoteric and difficult to understand.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Further

Reading: |

|

|

|

|

|

Kopp,

Carlo, The

E-Bomb Threat and WMD Terrorism, Interview with Dr. Karen Carth

for ISRIA, International Security Research & Intelligence Agency,

28th June, 2006.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Kopp,

Carlo, A Doctrine for the Use of

ElectroMagnetic Pulse Bombs, Air

Power Studies Centre Paper No.15,

Royal Australian Air Force, July 1993. (PDF 61691 bytes)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Kopp, Carlo,

The E-Bomb - A

Weapon of Electrical Mass Destruction, InfoWarCon 5 Conference Paper, Proceedings of InfoWarCon 5, NCSA,

September 1996 (PPT).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Kopp,

Carlo, An Introduction to the

Technical and Operational Aspects of the Electromagnetic Bomb, Air Power Studies Centre Paper No.50,

Royal Australian Air Force, November 1996. (PDF 394009 bytes)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ertekin,

Necati, E-Bomb:

The Key Element of the Contemporary Military-Technical Revolution,

MEng Thesis, Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, CA, September, 2008 (PDF).

|

|

|

|

|

|

Prischepenko,

Alexander B., Video

(Russian language): Electromagnetic Weapons: Myths and Reality,

Popular Mechanics Seminar, November, 2010.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Kopp,

Carlo, Hardening Your Computing

Assets, Technical Report, posted on infowar.com, March 1997

[previously published in Open Systems Review, February, 1997]. (HTML)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Kopp, Carlo,

Considerations

on the Use of

Airborne X-band Radar as a Microwave Directed-Energy Weapon,

Journal of

Battlefield Technology, vol 10, issue 3, Argos Press Pty Ltd,

Australia, pp. 19-25.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Neuber,

Andreas, Explosively

driven pulsed power: helical magnetic flux compression generators,

Google eBook, Springer Science & Business, 15/09/2005 - Science -

280 pages.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Benford,

James,

Swegle, John Allan, Schamiloglu, Edl, High

power microwaves, CRC Press, 05/02/2007 - Technology &

Engineering - 531 pages.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Landecker,

K.; Skattebol, L.V.; Gowdie, D.R.R., Single-spark

ring transmitter, Proceedings of the IEEE, Volume: 59

Issue: 7, July, 1971, pp 1082 - 1090.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Kopp,

Carlo, E-Bomb Frequently Asked

Questions (FAQ), Technical Note, posted on GlobalSecurity.org,

2003.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Commission to Assess

the Threat to the United States from Electromagnetic Pulse (EMP) Attack

/ Rep.

Roscoe Bartlett on Electro Magnetic Pulse

|

|

|

|

|

|

![Home - Air Power Australia Website [Click for more ...]](APA/APA-Title-Main.png)

![Sukhoi PAK-FA and Flanker Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/flanker.png)

![F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/jsf.png)

![Weapons Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/weps.png)

![News and Media Related Material Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/media.png)

![Surface to Air Missile Systems / Integrated Air Defence Systems Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/sams-iads.png)

![Ballistic Missiles and Missile Defence Page [Click for more ...]](APA/msls-bmd.png)

![Air Power and National Military Strategy Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/strategy.png)

![Military Aviation Historical Topics Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/history.png)

![Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance and Network Centric Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/isr-ncw.png)

![Information Warfare / Operations and Electronic Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/iw.png)

![Systems and Basic Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/technology.png)

![Related Links Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/links.png)

![Homepage of Australia's First Online Journal Covering Air Power Issues (ISSN 1832-2433) [Click for more ...]](APA/apa-analyses.png)

![Home - Air Power Australia Website [Click for more ...]](APA/APA-Title-Main.png)

![Sukhoi PAK-FA and Flanker Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/flanker.png)

![F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/jsf.png)

![Weapons Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/weps.png)

![News and Media Related Material Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/media.png)

![Surface to Air Missile Systems / Integrated Air Defence Systems Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/sams-iads.png)

![Ballistic Missiles and Missile Defence Page [Click for more ...]](APA/msls-bmd.png)

![Air Power and National Military Strategy Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/strategy.png)

![Military Aviation Historical Topics Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/history.png)

![Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance and Network Centric Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/isr-ncw.png)

![Information Warfare / Operations and Electronic Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/iw.png)

![Systems and Basic Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/technology.png)

![Related Links Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/links.png)

![Homepage of Australia's First Online Journal Covering Air Power Issues (ISSN 1832-2433) [Click for more ...]](APA/apa-analyses.png)

![Sukhoi PAK-FA and Flanker Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/flanker.png)

![F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/jsf.png)

![Weapons Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/weps.png)

![News and Media Related Material Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/media.png)

![Surface to Air Missile Systems / Integrated Air Defence Systems Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/sams-iads.png)

![Ballistic Missiles and Missile Defence Page [Click for more ...]](APA/msls-bmd.png)

![Air Power and National Military Strategy Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/strategy.png)

![Military Aviation Historical Topics Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/history.png)

![Information Warfare / Operations and Electronic Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/iw.png)

![Systems and Basic Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/technology.png)

![Related Links Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/links.png)

![Homepage of Australia's First Online Journal Covering Air Power Issues (ISSN 1832-2433) [Click for more ...]](APA/apa-analyses.png)