|

||||||||||||||||||||||

![Australia's First Online Journal Covering Air Power Issues [ISSN 1832-2433] Australia's First Online Journal Covering Air Power Issues [ISSN 1832-2433]](APA/APA-Title-Analyses.png) |

||||||||||||||||||||||

![Sukhoi PAK-FA and Flanker Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/flanker.png) |

![F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/jsf.png) |

![Weapons Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/weps.png) |

![News and Media Related Material Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/media.png) |

|||||||||||||||||||

![Surface to Air Missile Systems / Integrated Air Defence Systems Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/sams-iads.png) |

![Ballistic Missiles and Missile Defence Page [Click for more ...]](APA/msls-bmd.png) |

![Air Power and National Military Strategy Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/strategy.png) |

![Military Aviation Historical Topics Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/history.png)

|

![Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance and Network Centric Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/isr-ncw.png) |

![Information Warfare / Operations and Electronic Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/iw.png) |

![Systems and Basic Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/technology.png) |

![Related Links Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/links.png) |

|||||||||||||||

| Last Updated: Mon Jan 27 11:18:09 UTC 2014 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

![Australia's First Online Journal Covering Air Power Issues [ISSN 1832-2433] Australia's First Online Journal Covering Air Power Issues [ISSN 1832-2433]](APA/APA-Title-Analyses.png) |

||||||||||||||||||||||

![Sukhoi PAK-FA and Flanker Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/flanker.png) |

![F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/jsf.png) |

![Weapons Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/weps.png) |

![News and Media Related Material Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/media.png) |

|||||||||||||||||||

![Surface to Air Missile Systems / Integrated Air Defence Systems Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/sams-iads.png) |

![Ballistic Missiles and Missile Defence Page [Click for more ...]](APA/msls-bmd.png) |

![Air Power and National Military Strategy Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/strategy.png) |

![Military Aviation Historical Topics Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/history.png)

|

![Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance and Network Centric Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/isr-ncw.png) |

![Information Warfare / Operations and Electronic Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/iw.png) |

![Systems and Basic Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/technology.png) |

![Related Links Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/links.png) |

|||||||||||||||

| Last Updated: Mon Jan 27 11:18:09 UTC 2014 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

Revisiting

the

Lessons

of Operation Allied Force

|

|

A Serbian S-125 / SA-3 Goa

battery killed

an F-117A Nighthawk early in the OAF air campaign. Complacency was

clearly the single biggest contributor to this unprecedented combat

loss. A second F-117A suffered damage from a near miss SA-3 shot.

|

|

|

Air Power Australia Analysis 2009-04 14th June, 2009 A Paper by Martin Andrew, BA(hons), MA, PhD, RAAF(Retd) Text © 2009 Martin Andrew |

|

|

|

| The

Federal

Yugoslav

Integrated Air Defence System (IADS)

survived Operation Allied Force (OAF), the NATO air campaign used to

force the

removal of Serbian forces from Kosovo, which ran from 24th March

to 9th June, 1999, and at

its height involved over 1,000 aircraft. Survival

of the IADS was achieved by employing three different methods to

negate NATO’s

air power. The decision not to use

ground forces certainly made Serb defensive measures much easier. By deliberately not employing all their

defence assets at once, known as the strategy of withholding military

force, the

constant moving about of its mobile surface-to-air missile to ensure

they could

not be targeted, and the widespread

use of deception measures. |

|

The Successful Serbian Strategy of Withholding Military ForceThe strategy of withholding military force is different to a holding action, as it is an asymmetric strategy for a weaker force to withstand attacks upon its centre of gravity, was developed by the Communist Chinese to nullify the overwhelming air supremacy that the United States and its allies held in Korea. By withholding forces from action, in the event of attacks by superior forces, it can absorb more punishment than otherwise, which Mao referred to as ‘the breaking of pots and pans’.The strategy is particularly important in the context of air power, as by hiding resources and deliberately withholding them from action, the forces trying to locate them cannot destroy them. An air campaign can then become one of virtual attrition to the detriment of the aggressor, due to the wearing out of men and machines, for very little gain. Morale and public opinion aspects also come into play when there appears to be little or no results for the resources expended. A defending ground force needs to be forced to expose itself, thus allowing it to be attacked by air power. One option is to stage an attack that is designed to compel a defending force to react. An example could be the insertion of forces by air to embarrass the leadership into defending more areas. To enable air power to hunt down and then destroy targets requires robust Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (ISR) systems and Precision Guided Munitions (PGM). Terrain masking and deception measures by small forces in complex terrain, such as hilly and/or jungle terrain, as occurred in Kosovo and in the various conflicts in Southeast Asia, often negate the use of most ISR systems, presenting difficulties in locating and positively identifying targets. The locating, tracking and targeting of difficult to find targets often require quantities and technological capabilities of equipment beyond a country’s material resources. The aim of the OAF campaign was to force Serbian forces to stop attacks upon ethnic Albanians and leave Kosovo through the coercive application of air power alone. Air power was to be used, exclusively, to reduce casualties on the NATO side, which made life for the Serbian forces in Kosovo easier as there were no ground troops to worry about. By employing the strategy of withholding military force the Serbs avoided having their air defence and field units being destroyed in the first days of the air campaign. They had absorbed the lessons of Operation Desert Storm, and preserved their assets for the long haul, which was a successful strategy as Serb forces were still firing Surface-to-Air Missiles (SAM) on the last day of Operation Allied Force.[1] Employing passive systems such as electro-optical tracking equipment further enhanced the survivability of IADS components, by not creating an emission signature that NATO defence suppression aircraft could lock on to. [2] |

|

Problems

and

Issues

Surrounding the

Use of PGMs

Bad

weather and the rigid insistence on avoiding collateral damage and

casualties

to the

attack force dogged NATO planners. This

led to an over-reliance on Precision Guided Munitions (PGMs). In the

first three weeks of ‘Allied Force’ there were only seven days of

‘favourable

weather’ for air operations and ten days on which 50 percent of the

strikes had

to be cancelled due to the fear of collateral damage.[3] Ninety

percent of the

ordnance dropped were PGMs which also had

their own problems. Global Positioning System

(GPS) aided munitions, the only affordable all-weather munitions, can

be inaccurate due to

the

cumulative effect of numerous GPS

errors, as well as small inaccuracies in the targeting aircraft,

maps

and the

munition itself. This is

called the ‘sensor-to-shooter error budget’ in United States parlance.[4] Further,

the amount of

cloud over Kosovo caused many laser-guided bombs (LGBs) to ‘lose lock’

and ‘go

rogue’ often landing kilometres away from

their intended

target.[5]

The reliance on GPS guided bombs caused a shortage that became so acute in late April that the GPS guided Joint Direct Attack Munitions (JDAM) were available for only the B-2A Spirit bomber.[6] By late April the ratio of PGMs to unguided munitions used had dropped to 69 percent.[7] Many of the targets struck by PGMs in Kosovo were not judged to be worth the then $US12,000 cost of the Paveway II LGB kits, and could have been hit safely by unguided ordnance.[8] The fire control avionics fitted to most NATO aircraft enabled very accurate bombing using ‘dumb’ bombs, albeit with a necessary reduction in bombing altitude. Serbian ground forces were hard to locate due to their small unit size and movement, generally being company sized units of between 80 to 150 personnel, and around six armoured vehicles, operating autonomously or semi-autonomously of each other. Using the woods and mountains, and by not being a large target or moving in a set direction, did not allow an intelligence picture to be easily built up, and thus made these forces difficult to locate from the air.[9] NATO's insistence upon avoiding collateral damage at all costs by using precision guided munitions, and the Serbian operational doctrine of hiding their forces, impacted the outcome. The resulting effect of these two strategies was ‘virtual attrition’, through the cost of the munitions expended and the accrued wear and tear on the aircraft employed. The air campaign over Kosovo severely affected the readiness rates of the United States Air Force’s Air Combat Command during that period. Units in the United States were the most badly affected, as they were were stripped of their personnel and spare parts to support ACC (Air Combat Command) and AMC (Air Mobility Command) units involved in Operation Allied Force. The Commander of the USAF’s Air Combat Command, General Richard E Hawley, outlined this in a speech to reporters on 29 April, 1999.[10] Further, many aircraft will have to be replaced earlier than previously planned, as their planned fatigue life was prematurely expended. PGM inventories needed to be re-stocked, the warstock of the AGM-86C Conventional Air-Launched Cruise Missile dropping to 100 or fewer rounds.[11] Of the more than 25,000 bombs and missiles expended, nearly 8,500 were PGMs, with the replacement cost estimated at $US1.3 billion.[12] Thus the USAF suffered from virtual attrition of its air force without having scored a large number of kills in theatre. Even if the United States' best estimates of Serbian casualties are used, the Serbians left Kosovo with a large part of their armoured forces intact. |

|

|

Serbia operated a wide range of

former Soviet and indigenous point

defence weapons, which presented genuine risks to NATO aircraft

loitering at low altitudes. This forced bombing from higher altitudes,

which drove up the demand for PGM warstocks, and imposed severe weather

restrictions.

The Yugoslav Army operated a small number

of Soviet supplied 9K35 Strela 10 / SA-13

Gopher heatseeking SAM systems, carried on an indigenous chassis rather

than the Soviet supplied MT-LB chassis. The indigenous S-10MJ Sava

variant is carried on a fully amphibious chassis.

The Soviets

supplied no less than 113 9K33 / SA-9 Gaskin heatseeking missile

systems to Yugoslavia.

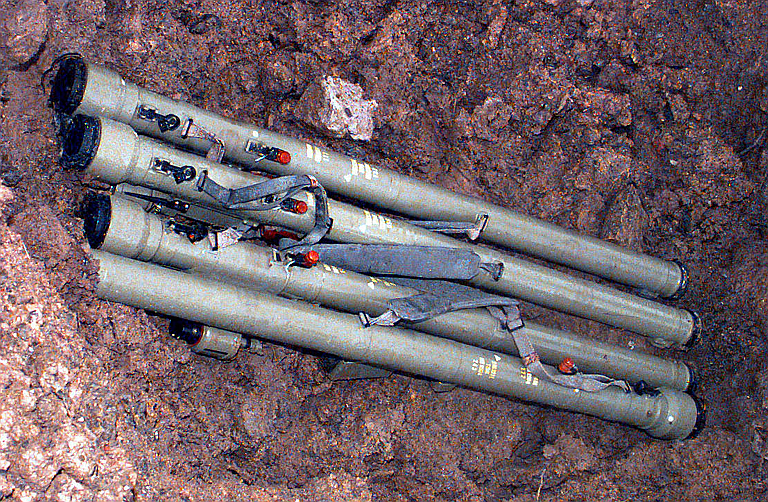

The Serbian forces in Kosovo were well

equipped with licence built legacy Soviet 9K32M / SA-7B Grail MANPADS,

and a small number of Kazakh supplied 9K310 Igla-1 / SA-16 MANPADS. The

depicted SA-7B rounds

were confiscated and destroyed. The total MANPADS inventory was cited

at ~850 rounds (US DoD).

The Serbians improvised two point defence weapons, based on the Soviet supplied R-60 / AA-8 Aphid (below) and R-73 / AA-11 Archer (above) air to air missiles. The RL-4M used a single Archer, the RL-2M a pair of Aphids. Both designs used the Praga M53/59 SPAAG vehicle and neither appear to have been used with any operational effect. According to JMR, the designs were produced by the VTI (Vojno-Tehnicki Institut = Military Technical Institute) and VTO (Vazduhoplovno-Opitni Centar = Air Force Testing Centre).   In addition to the ubiquitous Soviet S-60

57 mm AAA gun, the Yugoslav Army operated fifty four Soviet supplied

ZSU-57-2 SPAAGs in 1999. In total Servia deployed around 1850 AAA

pieces (US DoD).

The licensed Czechoslovak Praga M53/59

twin 30 mm SPAAG was widely used during the Balkans conflict,

especially against soft-skinned ground targets. Based on the WW2 Flak

38 design, the ‘Praga’ is equipped with two PDLVK automatic guns and an

optical sighting system. Around 100 remained in service during OAF

(image via http://www.tanksforsale.co.uk/).

The indigenous BOV-3 SPAAG was widely used

by the Yugoslav Army. It is armed with three M55A4B1 20 mm automatic

guns.

|

|

Successful

Deception

Measures

Sun

Tzu wrote that all warfare is based on deception and Serbian deception

measures

were very successful. Decoys

were a real problem for strike aircraft, as loitering over an area at

low altitudes made

them

targets for MANPADS, infrared guided point defence SAMs such as the

SA-9 Gaskin and SA-13 Gopher, and SPAAGs such as the ZSU-23-4P,

BOV-3/30 series and the Praga M53/59.

At least 16 decoys were hit that were thought to be real targets, and a further nine decoys were also deliberately hit, so pilots would not loiter over them trying to discriminate between them and real targets.[13] They also used up valuable airframe hours, and the incurred attendant increased logistical costs. Air forces have not always had invested sufficiently in sensors to counter deception and camouflage techniques, which the Serbs exploited quite successfully. This was noted quite early in the post ‘Allied Force’ after-action study.[14] NATO flew approximately 3,000 sorties over Kosovo, and just under 2,000 of these saw ordnance expended.[15] These sorties were claimed at the time to have destroyed 93 tanks and 153 armoured personnel carriers (APCs) out of the approximately 350 tanks and 440 APCs believed to have been in Kosovo.[16] NATO also claimed to have hit 339 military vehicles and 389 artillery pieces and mortars. [17] These figures were widely off the mark as General Clark, the Operation Allied Force commander, conceded that not all targets hit were destroyed, and that only 26 tanks could be confirmed as kills.[18] |

|

|

Serbian IADS SAM Systems

Serbia operated a mix of

obsolescent and often time-expired Soviet era S-75 / SA-2 Guideline,

S-125 / SA-3 Goa and 2K12 / SA-6B Gainful area defence SAMs for the

protection of critical infrastructure and fielded military forces.

While these SAM systems did not inflict high losses on NATO aircraft,

with a reported 665 SAM rounds fired for two verified kills, the

inability of NATO to inflict decisive attrition upon the IADS resulted

in ongoing

high operational costs due to the need to keep EA-6B Prowler, RC-135V/W

Rivet Joint, Tornado ECR and F-16CJ Weasels airborne during any

significant operations over the territory of the rump FRY.

By far the most survivable of all Yugoslav

SAM systems, only three of the twenty two 2K12 Kvadrat / SA-6B

Gainful SAM 1S91 Straight Flush radars were destroyed by NATO forces.

With a genuine 5

minute shoot-and-scoot capability, the twenty two batteries of Kvadrat

systems

were able to evade NATO

Tornado ECR and F-16CJ aircraft very successfully (Image © Miroslav

Gyűrösi).

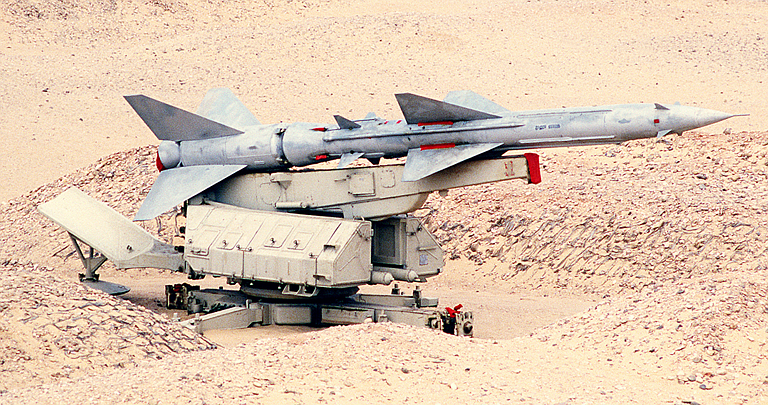

The primary

SAM system in the Yugoslav IADS was the semi-mobile Soviet supplied

S-125 Neva / SA-3 Goa, some of which were subjected to

upgrades prior to OAF, involving a thermal imager and laser rangefinder

on the SNR-125 Low Blow. Fourteen batteries were in operation at the

beginning of OAF. An S-125 battery successfully downed an

F-117A Nighthawk early in the campaign, and damaged another. Operated

from fixed sites, 80

percent of the S-125s were claimed destroyed [additional imagery here]

(Image © Miroslav

Gyűrösi).

Serbia

is claimed to have modified a number of its legacy Soviet supplied S-75

Dvina / SA-2

Guideline SAM systems. Like the SA-3 Goa, the three SA-2 Guideline

batteries were

operated primarily from static sites and suffered losses to around 2/3

of the force (US DoD).

At a

Russian airshow subsequent to OAF, a Russian senior engineer complained

to a visiting US analyst, that Russian digital upgrades covertly

installed in some of the P-18 Spoon Rest radars operated by Serbia were

subsequently sold to China (image © Miroslav Gyűrösi).

|

|

Fixed

Air

Defences

Crippled But Mobile

Air Defences Survived

NATO

air planners were certainly concerned that not as many Serbian SAM

batteries were

destroyed, as they would have liked, with the then commander of the

United

States Air Forces in Europe (USAFE) acknowledging the success of

Serbian SAM battery shoot-and-scoot

operational tactics.[19] Mobile systems suffered few

casualties but the fixed defences were smashed. Two of

Serbia’s three static S-75 Dvina / SA-2 Guideline SAM battalions and 70

percent of their static S-125 Neva /

SA-3 Goa SAM

sites were destroyed as compared with only three of their 22 mobile 9M9

Kvadrat / SA-6 Gainful SAM

systems.[20]

Serbia certainly left Kosovo, and suffered a tremendous amount of damage to its infrastructure in Serbia, yet in the face of an air campaign that at the end numbered over 1,000 aircraft, Serbian combat power remained substantially intact. The number of sorties generated by the NATO forces, particularly the United States Air Force, left them short of spare parts and munitions, required increased maintenance, and a force reduced in effective size due to the decreased fatigue life of many aircraft. This virtual attrition, with little relative destruction of the opposing forces, has shown that the Serbian military strategy was successful, even if the Milosovic regime did not achieve its political objectives. |

|

Conclusion

The strategy of

withholding military force in Kosovo was a military success, even if it

did not prevent a political failure. Serbia retained its ground combat

strength, in

the face of overwhelming air power, and the Kosovo Liberation Army was

disarmed as part of the political settlement.

The first key lesson the campaign produced, was that an opposing ground force must be driven out from cover, to induce the concentration of force required to facilitate efficient targeting and destruction by firepower. The need to keep NATO casualties to an absolute minimum was the reason for the decision not to deploy ground forces, but as shown earlier in this paper, this reduced the effectiveness of the air campaign. The Serbian forces used their freedom of movement to maximum advantage. The second key lesson of the war was the effectiveness of the passive air defence measures, especially mobility and decoys, on the air campaign itself. A NATO squadron commander, who reviewed the original 1999 version of this paper, said the paper should emphasise decoys more as they were a huge problem during the campaign. This was explored in the second section of the paper, but the discussion was limited by the open source material available at that time. The Russian military certainly took notice of Operation Allied Force and this is reflected in fundamental doctrinal and technological changes in their approach to operating and designing air defence systems. There is much new equipment, primarily of Russian and Chinese origin, but also from Belarus and the Ukraine, now available on the open market as building blocks, for any country with enough money and the motivation, to create a highly survivable Integrated Air Defence System[27]. This equipment includes both passive and active, and soft and hard kill measures as part of the air defence network, including transportable GPS/GLONASS jammers, decoy radar emitters, active defensive countermeasures for radars, ISR radar and airborne communications jammers, and point defence missile systems designed to intercept anti-radiation missiles such as the HARM and ALARM, and Precision Guided Munitions such as the JDAM and JASSM. However, the biggest lesson learnt by Russian strategists was the need to be able to ‘shoot and scoot’ like self-propelled artillery. Stealth, reduced sensor-to-shooter times and GPS guided munitions were already making the older fixed air defence systems obsolete prior to Allied Force and the Russians realised many of their systems were vulnerable. Operation Allied Force showed mobility was the key element to survivability, as the fourth part of the paper shows. |

|

|

Mobility - The Most Important Lesson of

Operation Allied Force

Following OAF, Russian industry

launched a campaign to provide high mobility capabilities to all new

build, and many legacy SAM systems and radars.

Above: Defense Systems upgraded mobile

SA-3 TEL. Below: Cuban SA-3 TELs in foreground, SA-2 TELs in background

(Said Aminov, Vestnik-PVO).

High mobility is characteristic of new

build equipment from Russia and former Soviet republics. Above: the new

Vostok E radar can stow or deploy in 6 minutes. Below: NNIIRT's

new Nebo M VHF band radar on a high mobility BAZ-6909 series

chassis.

|

|

Further

Observations

|

|

Endnotes/References: [2]

. Wall,

R. ‘SEAD

Concerns Raised in Kosovo’, Aviation Week

& Space Technology, Vol. 151, No. 4, 26 July

1999, p. 75.

[3]

. Cook,

N. ‘NATO

battles against the elements’, Jane’s

Defence Weekly, Vol. 31, No. 16,

[4]

. Cook,

N. ‘NATO

battles against the elements’, Jane’s

Defence Weekly, Vol. 31, No. 16, 8 June 1999, p. 4.

[5]

. Bender,

B. ‘Kosovo lessons won’t mean

big changes by USA’, Jane’s

Defence Weekly, Vol. 32, No. 2, 14 July

1999, p. 3.

[6]

. Fulghum,

D.A. “Bomb shortage crimps

Air War’, Aviation Week & Space Technology, Vol. 150, No. 18,

3 May 1999, p. 22.

[7]

. Fulghum,

D.A. “Bomb shortage crimps

Air War’, Aviation Week & Space

Technology, Vol. 150, No. 18,

3 May 1999, p. 22.

[8]

. Patterson,

J.J. ‘Smart Bombs and Linear

Thinking Over Yugoslavia, United States

Naval

[9]

. Mann,

P. ‘NATO Arraigned For ‘Strategic

Miscalculation’’, Aviation Week &

Space

Technology, Vol. 150, No. 8, 3 May 1999, p. 22. [10]

. ‘Hawley’s

Warning’, AIR FORCE Magazine, Vol. 183, No. 7, July 1999, p. 57.

[13]

. Aviation Week

& Space Technology,

Vol. 151, No.12, 20 September 1999, p. 25; ‘NATO

[15]

. ‘NATO assesses Kosovo

air campaign’, Jane’s Missiles and

Rockets CD-ROM , Vol. 3, No. 10,October 1999.

[16]

. Walker,

J. “NATO denies it bombed in

the Balkans’, Weekend Australian, 18 –

19 September

[19]

. Grant,

R. ‘Airpower Made It Work’,

AIR

FORCE

Magazine, Vol. 82, No. 11,

November 1999, p. 34.

[20]

. ‘Yugoslavian

air-defence system withdrawn from Kosovo, Jane’s Missiles and Rockets,

Vol. 3,

[21]

. Kosovo: Lessons

from the Crisis,

Ministry of Defence, London, 2000, http:///www.mod.uk/

[22]

. ASTOR Sentinel R1

Airborne Stand-Off Radar, airforce-technology.com, http://www.airforce-

[23]

. ‘Brimstone

Advanced Anti-Armour Weapon’, MBDA

Solutions, http://www.mbda-

[24]

. Kosovo: Lessons

from the Crisis,

Ministry of Defence, op.cit.,

p. 51.[25] Steven

J.

Zaloga, The

Evolving SAM Threat: Kosovo and Beyond,

Journal of Electronic Defense, May 2000, http://pvo.guns.ru/combat/zaloga_kosovo.htm

[26] Seymour Johnson, Yugoslavia's secret SAMs, Janes Missiles and Rockets, 05 April 2005, http://www.janes.com/defence/news/jmr/jmr050405_1_n.shtml. [27] A number of Air Power Australia reference pages detail technologies now available for the design of survivable IADS. Refer especially pages on Ground Based counter ISR ECM systems, Air Defence System Defensive Aids and Point Defence Weapons. |

|

Recommended Reading:

|

|

Air Power Australia Analyses ISSN 1832-2433 |

|

|

|||||||||||||

![Sukhoi PAK-FA and Flanker Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/flanker.png) |

![F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/jsf.png) |

![Weapons Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/weps.png) |

![News and Media Related Material Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/media.png) |

||||||||||

![Surface to Air Missile Systems / Integrated Air Defence Systems Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/sams-iads.png) |

![Ballistic Missiles and Missile Defence Page [Click for more ...]](APA/msls-bmd.png) |

![Air Power and National Military Strategy Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/strategy.png) |

![Military Aviation Historical Topics Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/history.png)

|

![Information Warfare / Operations and Electronic Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/iw.png) |

![Systems and Basic Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/technology.png) |

![Related Links Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/links.png) |

|||||||

![Homepage of Australia's First Online Journal Covering Air Power Issues (ISSN 1832-2433) [Click for more ...]](APA/apa-analyses.png) |

|||||||||||||

| Artwork, graphic design, layout and text © 2004 - 2014 Carlo Kopp; Text © 2004 - 2014 Peter Goon; All rights reserved. Recommended browsers. Contact webmaster. Site navigation hints. Current hot topics. | |||||||||||||

|

Site Update

Status:

$Revision: 1.753 $

Site History: Notices

and

Updates / NLA Pandora Archive

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

Tweet | Follow @APA_Updates | |||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||